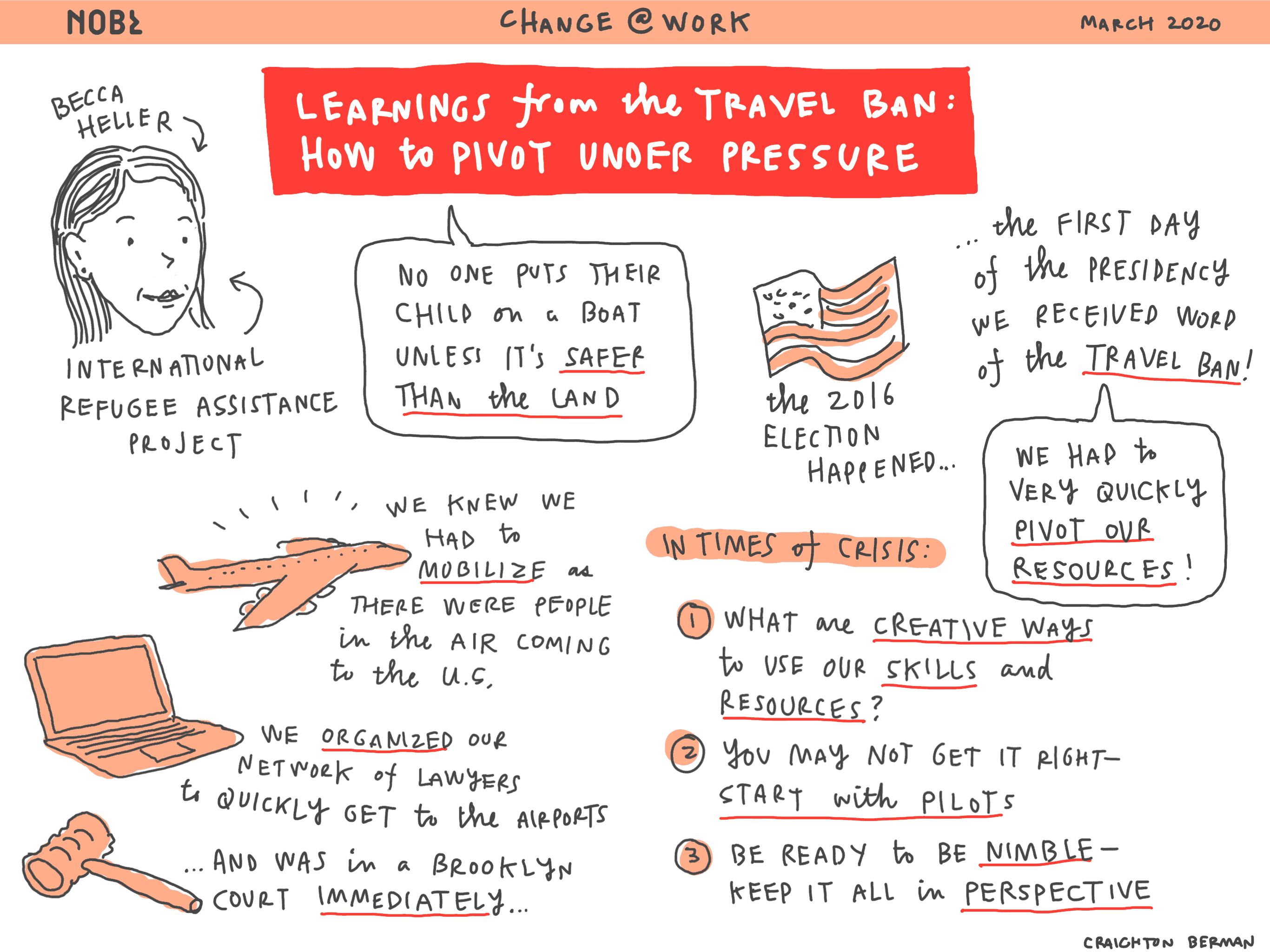

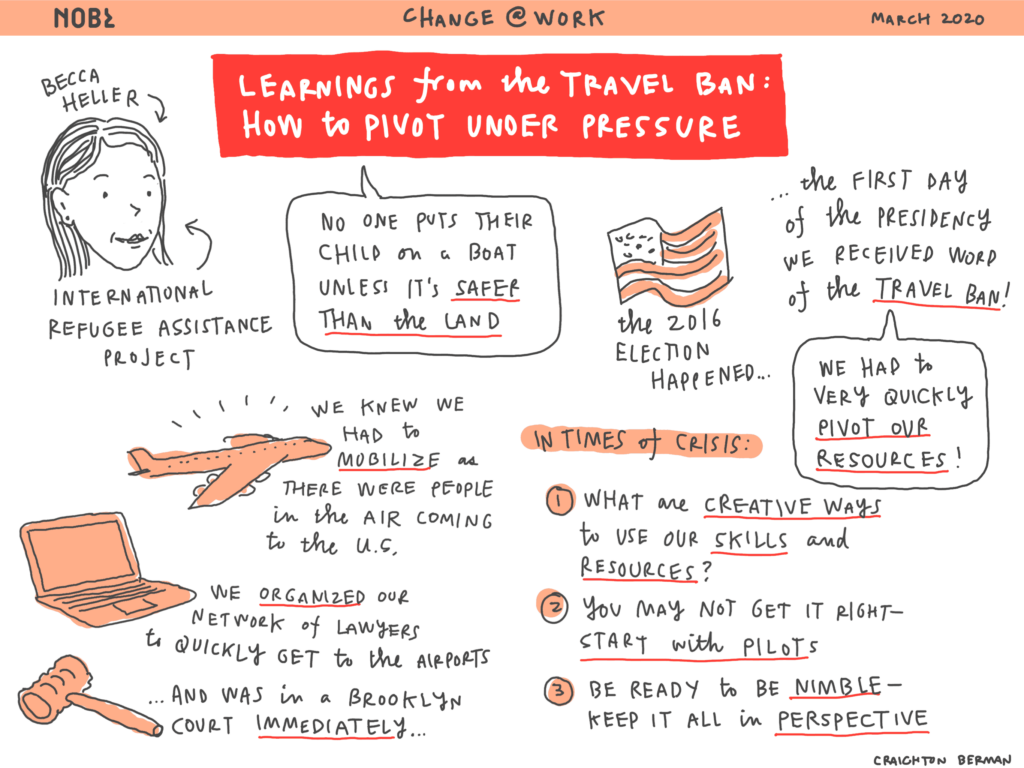

In her role as Executive Director of the International Refugee Project, Becca Heller organized lawyers to go to airports during the “Muslim Ban” (Executive Order 13769). At the Change@ Work 2020 conference, she shared the key lessons her team learned about innovating during the crisis:

- Listen to your staff. The people on the front lines are often the best equipped to bring innovative ideas and fresh perspectives.

- You’re not going to get it right (at first). Experiment at a small scale with pilots. 50-60% will fail, but if you’ve only invested a little, you’ll quickly know what to chase and what to abandon.

- Put it in perspective. For many of her refugee clients, upheaval is nothing new—they’ve dealt with life being suddenly turned upside down before. Remembering that people are resilient can put your own challenges in perspective.

- Don’t panic. When in crisis, provide accurate, calm, timely, and relevant information provided in a way your clients can trust.

Read the Transcript

Becca Heller:

So as is probably happening to most people, there is like a 20% chance that I will get interrupted by my child at some point. Although my in laws and her father have promised to try to keep that under control. So premature apology if that occurs. I’m going to talk about sort of what our response was as an organization helping refugees predominantly from the Middle East when Trump was elected and then when the travel ban came down. And I think anyone is free to take any lessons they want.

I’ll talk about a couple of lessons that I took. Obviously like no crisis is the same as another crisis, so I don’t expect our experience to be universally applicable. But maybe it’ll be helpful or maybe it’ll just be interesting. So I run an organization called the International Refugee Assistance Project, and we provide legal assistance to folks who are outside the U.S. or outside of Europe, who are in really unsafe situations and are trying to get across the border to some kind of safety.

We’re particularly focused on helping people legally cross the border, because we don’t think that anyone really wants to cross the border illegally. There’s a really beautiful poem called Home by a British Somali poet named Warsan Shire, and it’s about what it’s like to flee home, and the first line of it is, “No one leaves home unless home is the mouth of a shark”. And then one of my favorite lines in it that’s gotten a lot of play is, “No one puts their child in a boat unless the water is safer than the land.”

So people fleeing don’t want to be fleeing, they don’t want to leave home, they don’t want to get on a raft in the Mediterranean or hire a coyote across the Sonora Desert. But there hasn’t been a major intervention to say, what options are really legally available for you and how can we help you come here safely in a way that’s in your best interest, and respects your human rights, but also is in the best interest of the national security of the countries that you’re coming to, who really would prefer for immigration to be legal.

A huge focus of ours starting in 2014, 2015 was Syrian refugees. We had tons and tons of clients who were Syrian refugees in a variety of really challenging situations. And I was really convinced that Hillary was going to be elected president, as I think were a lot of people, because apparently I had no idea what was happening in the middle of the country. And so we had this whole new program around climate change and migrant displacement plans. We were really excited for that pivot.

And then Trump was elected and he doesn’t believe in either immigration or climate change, and ran on a really expressly xenophobic platform that included banning all Syrian refugees from coming to the U.S. And obviously his election was really traumatic for me. It was really traumatic for a lot of people. We were deeply worried about the impact that it would have on our clients. And so the first couple of days, I think I was just sort of like catatonic and probably drunk.

And then after that I was sort of like, “Okay, how do we start making a game plan?” And the question we asked ourselves was, “Even though our work as normal can’t continue as is, right? Assuming that there’s going to be sort of dramatic restrictions on immigration and on refugees, and so we can’t just be sort of helping people through the system all the time. What resources do we have that we might be able to apply to this crazy new world that we’re anticipating?”

And the way that our model works is that we have staff working on cases, but we also have volunteer attorneys at over a hundred law firms, and then law student chapters at 30 law schools in total we had I think like 2000 or 3000 volunteer law students and lawyers working on cases at the time. And we’re like, “Well we have this army of lawyers and they know how important it is to advocate for refugees. And so what are some of the ways that we can deploy them?”

And we really spent kind of November to January thinking about what are the tools that are in our toolbox? Maybe we’ve been using them for one thing, but is there another thing that we could be using them for? Right? A small analogy would be the fact that the Tesla factory is now going to make masks or ventilators, I forget which one it is. But sort of saying, “How can we reapply what we already have to apply to sort of the new world we live in?” I think also in that time period, there were a lot of people sort of pushing a narrative that Trump had run on a way more right or far right platform than he really believed in, that Ivanka and Jared would somehow be this moderating force, this Muslim ban that he had threatened wasn’t actually going to occur.

And he was sworn in on Friday, January 20th, he took the weekend off to golf. And so the first real full working day of the presidency was the following Monday. And literally that day, kind of the first day of the presidency, someone leaked to us the text of the Muslim ban. Someone took a photo of the text on the monitor of a desktop computer in the White House and through a couple of different people, it ended up in our hands. And we were like, “Oh he wasn’t kidding. He’s going to do this right away and this is the first thing he’s going to do.”

So we started trying to triage. We’re like, “Okay, what are the immediate effects of this on our clients?” And we realized it would be that they couldn’t come in anymore. So we have a lot of clients actually who already had permission to come to the U.S. and a large number of them actually were Iraqi and Afghan interpreters whose lives were at risk, because they had worked for the U.S. Military in those countries, and they were coming in under a special program that Congress created to protect them from the threats against their life by groups like the Taliban.

And so we called all of our clients who had valid permission to enter but hadn’t left yet. Because as I think people have found out recently, and as I found out, we last week left Brooklyn and came to Michigan. We wanted to be with my in laws, because we could have some childcare help and we wanted to be able to support them if something happened. We wanted to be in a place that had some outdoor space. But I thought a lot about my clients because we’re packing up our car and we’re not sure when we’re coming back.

And I’m not trying to compare that experience to the experience of fleeing like war-torn Syria. But it does take a minute to kind of leave what you know, and get your whole home together and get your family together. And in the case of our clients, they’re leaving forever. So we had a decent number of clients, about a couple of dozen who had valid permission to come to the U.S. but hadn’t departed yet. And we called everyone and we said, “The doors to America are closing. We don’t know when you need to get on a plane.”

And a bunch of people did. And then every day that week we weren’t sure kind of when this ban was going to come down. Every day there was a rumor that it was going to come down. I remember John Kelly was sworn in as Secretary of Homeland Security, and there was a rumor that the Muslim ban would be assigned that day to celebrate him signing on. And two days after that we had a client who was transgender, who was going to land in Los Angeles. And we have a lot of trans clients, because we try to focus on folks who are particularly vulnerable. So that means a lot of LGBTI cases.

And normally with trans clients I worry a lot about how safe they are kind of exiting the country there. And so if you are transgender in Saudi Arabia for example, it is not an option to go get new identification documents that match your new identity because you will get killed, literally. So you end up with trans clients it’s a woman, but her passport says that she’s a man. And maybe she goes by the name Becca, but her passport says that her name is Daniel. And so you worry that someone will get pulled aside for having allegedly fraudulent documents just because they’re kind of expressing who they really are.

And normally we would worry about that on exit. Right? We would worry about it with sort of more draconian countries like Saudi Arabia or Iraq or Syria. In this case, I was really worried about entry because I was like, they’re going to be looking for any excuse to mess with folks and especially refugees coming in from the Middle East. And I’m really worried that when she takes off from the Middle East, maybe she’ll be okay. But what happens if the travel ban comes down while she’s in the air?

So we decided that we were going to have a lawyer just kind of quietly hang out in the arrivals’ area of LAX, and that he and our client would be sort of WhatsApping, and then if anything happened we would have someone at the ready to file whatever was necessary. And thankfully she made it in without too much trouble. But that night at like 11:30 PM I was G-chatting with my policy director, Betsy Fisher, and we’ve since gone back and re-read this G-chat, and we both sound really drunk, although we were not, I think we were just tired and overwhelmed.

But basically, Betsy was like, “Oh, it’s a good thing that the band didn’t come down today.” And I was like, “Oh, why? Because our client was able to make it in?” And Betsy was like, “Yeah. And all the other refugees who would’ve been on the plane.” Because they tend to travel refugees in groups. And in that moment, I think we both simultaneously realized that apart from just refugees, whenever this ban came down, there were going to be literally like tens of thousands of people mid air who when they departed had permission to come to the U.S. but when they landed would essentially be undocumented immigrants, and nobody knew what was going to happen to them.

So we decided to sort of take our play of having a lawyer at the airport, and see if we could replicate that across the country. So we put out a call, and we organized lawyers to go to airports all over the U.S., we created a Google form and we had like 1600 signups in 45 minutes. And then the form crashed and the thing started kind of taking on a life of its own. And finally that the ban itself came down on Friday afternoon, January 27th it was signed at about 4:30. It seemed like things were pretty quiet. And then at 8:30 I got a call that one of our clients, Hamid Darwish, who had spent 10 years as an interpreter for the U.S. Military in Iraq had been detained.

They let out his wife and kid to tell his lawyer who was waiting that he was shackled to a table with a bunch of other people in a room at JFK Airport, and that they wouldn’t let him out. So we got together with Yale Law School, the ACLU and the National Immigrant Law Center, and we started putting together a lawsuit essentially saying, “You can’t turn airports into black sites. You can’t hold people at airports with no trial and not let them out. That’s not what an airport does. That’s a violation of U.S. law.”

And, we stayed up all night working on it so that we can file it at 5:30 AM because we wanted to on file before any international departures could take off, because we wanted to make sure that no one could be deported. We managed to get an emergency hearing in Brooklyn that night at 7:30 and at 8:30 the judge issued a ruling demanding that anyone being detained at an airport be released.

So it took us about 28 hours from when the ban was announced to winning a court victory, saying that people couldn’t be detained under the ban. And we only found out later through lawsuits under the Freedom of Information Act that as a result of that court order, 2,100 people were released from airport detention. Obviously the Muslim ban goes on to have a much longer story and is still in effect today, due to a really broad ruling by the Supreme Court. But I just want to draw out sort of three main things I took from that, because I know we have about two minutes left.

So the first is, when things change really radically, obviously we have to make some behavioral adjustments, but I think that workplaces don’t have to completely pivot to something else. I think it’s really important to say what are the skills and the resources that we have. And then spend time thinking about what are creative ways that we can apply them to this new set of problems that we’re facing. And for people who run organizations, I think it’s really important to listen to staff on this, because they’re going to be the closest to the actual kind of program that’s happening. They’ll have the best ideas of what skills and resources are there and then work together to say, “How do we apply these to this brave new world we live in?”

The second point I want to make is that you’re not going to get it, right. Right? No one knows what’s happening in a bunch of areas. We’ve found it really useful in the past three years to experiment with pilots, because we have a lot of ideas about maybe this’ll work, or maybe this’ll be helpful, or maybe we could do this. And so we start doing it on a small scale, and maybe 50 or 60% of the time it ends up not working.

But because we only invested a little bit and did it on a small scale, we’re able to then say, “Okay, we won’t do this anymore.” But the 40 or 50% of the time that it does work, suddenly you have something larger that you can kind of build on and scale up. So the fact that everything is in flux is really difficult in some ways, but it’s also a chance to really be creative and try things, and make small investments and things and keep a critical eye on sort of what you want to chase that’s successful, and what you want to kind of abandon.

Just the last thing I want to say is that… And this is a less of a kind of how to run an organization point and more of just a thing I’m thankful for is, I’ve been really inspired by the resilience of our clients. We’ve been in touch with a lot of them in the last week or two. People are obviously scared, people are in camps where there’s not soap or adequate hand-washing.

But I found that for many of our refugee clients, upheaval is not new to them. And so while they’re nervous and they’re seeking information, and they need referrals for services, the idea of life kind of being suddenly turned upside down, is something that they’ve dealt with a lot of times before. And the kind of equanimity with which they’re approaching it, in way harder circumstances than I’m in, has really allowed me to keep going, and to put in perspective that I’m in a house in Michigan and I’m okay, and I’m going to ride this out the same way that our clients have written out so much before.

Lucy Chung:

Becca, thank you so much and I’m just going to echo some of the comments. You’re a hero. Thank you for all this work. Thank you so much for sharing that story. I want to ask a couple questions that came in. You started to touch on this with the upheaval, etc., and I think this feels really applicable with so much uncertainty that your clients are often facing. How do you keep your clients feeling hopeful? What do you say in terms of balancing the very valid fear that they have with some optimism?

Becca Heller:

So we’re lawyers and I think it’s really important for us to sort of know that, and stay in our lane. It’s really not our job to give our clients hope, it’s our job to give them information, and it’s our job to give them accurate information. And I think that you could draw some parallels there between responsible governance during COVID, and public statements and that I think when you’re in crisis, the most helpful thing to get is calm, timely, accurate information.

So I don’t try to mess with my client’s emotions one way or the other and try to make them feel more hopeful, or less helpful or more cautious. I think refugees are sort of by definition some of the most badass people in the world, right? They’re people who went through just crazy ass shit, that we can’t even imagine and then got themselves out. So they don’t need me telling them how to emotionally adjust, what they need is just accurate, timely information delivered in a professional way that they can trust. And I think that’s pretty true of all of us right now and I wish that we were all getting that.

Lucy Chung:

I really appreciate that perspective. And then for you, how do you manage the intensity and the emotionality for yourself? I would imagine that hearing from your clients on a daily basis would take a toll. What do you do to manage that stress?

Becca Heller:

I mean, I think the big thing for me is a kind of existential thing that at least we’re doing something. Obviously there’s a lot of injustice in the world, and there’s a lot of really tough things going on, and we can’t solve them except for collectively. But I think for the staff and I, it’s really positive at least to feel like you’re dedicating your day to trying to make a difference.

We make sure that we share case victories all the time. So we had two brothers who had been separated from their mother, and their sister for five years. They arrived in the U.S. yesterday. And we sent out a picture to the staff of them hugging and it was just… It’s really good I think to… Obviously there’s a lot of tragic moments, and they can overwhelm you. But I think that’s why it’s important to really dwell on and take happiness in the good moments and in the successes, because it helps to give context, and it helps you keep going through the moments that are harder.

Lucy Chung:

I think that’s too perfect of a note to… There’s a lot of good questions, but that feels like a really nice note to end on. Everyone is saying plus one to sharing these victories, and plus one to the balance. Thank you so much, Becca. Truly, thank you. It’s really an honor to be able to speak to you about this.

Becca Heller:

Thanks for having me.

Lucy Chung:

Thank you.

Becca Heller:

Good luck to everyone and wash your hands.