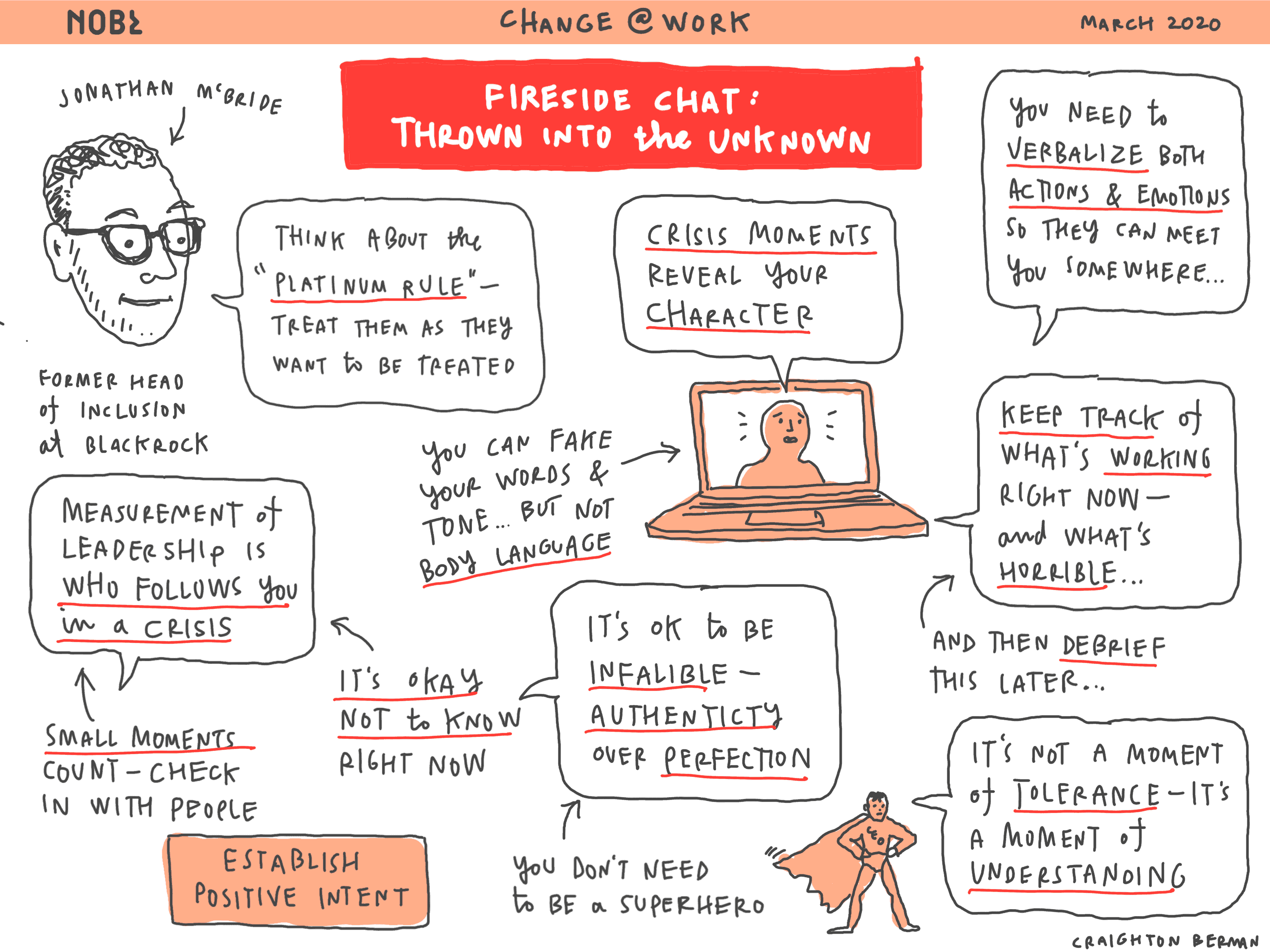

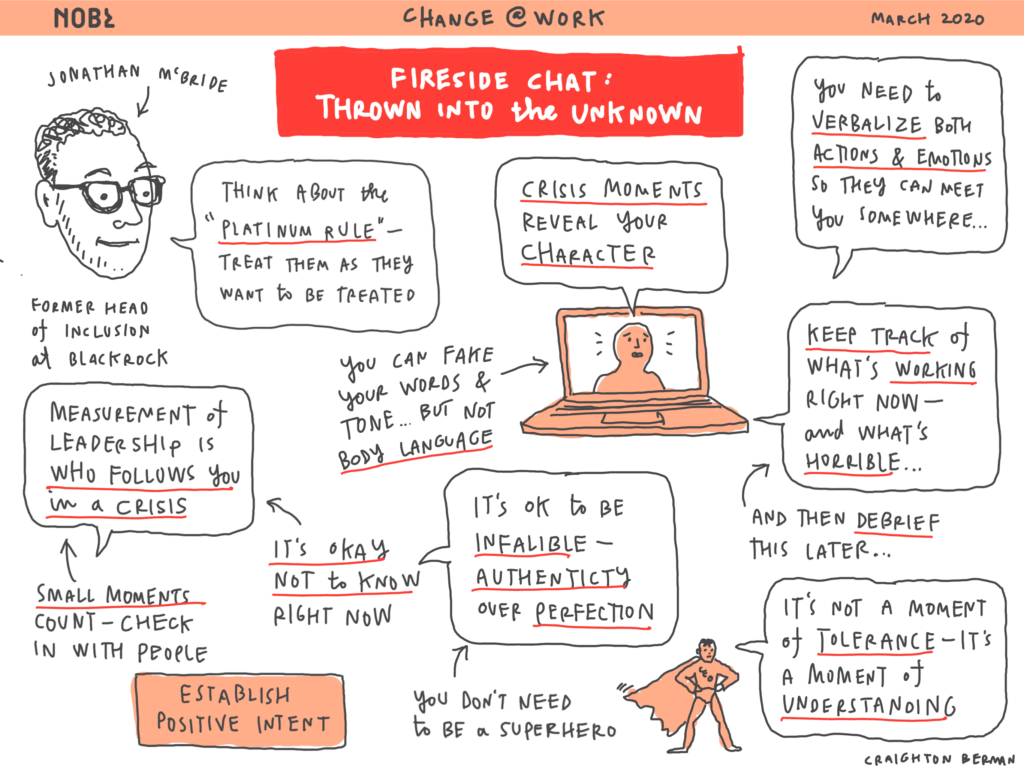

Leading his team through September 11th taught Jonathan McBride, former Head of Inclusion & Diversity at BlackRock, key lessons that apply to anyone facing a crisis:

- Put humanity first. In times of stress, treat people the way THEY want to be treated. Bring the team together and ask, “what’s the one thing you need to do to keep yourself sane?” Then, ask everyone to hold each other accountable, either by helping others do what they need, or by calling them out for not doing what they’re supposed to.

- Admit you’re fallible. If you’re feeling lost and that you don’t know what to do at the moment—don’t worry, no one does. Remember Brene Brown’s admonition that “vulnerability is our most accurate measure of courage” and work with your team to overcome obstacles together.

- Decide what not to do. Your to-do list at this time may feel overwhelming, but you don’t have to do everything at once. Pick two things to stop doing, and move on from there. In a way, times of crisis gives teams freedom—they don’t necessarily have to adhere to the bureaucracy and limitations of “business as usual.”

Read the Transcript

Lucy Blair Chung:

Jonathan is the former head of Inclusion & Diversity at BlackRock. He was also a former head of personnel for President Obama and was also an entrepreneur, and he’s going to tell us a little bit about that. So let’s just jump right in. When we chatted, you told us a good story for this time about running a company during September 11th.

Jonathan McBride:

Yeah. Thanks, Lucy, and we can go back… Also, by the way, I was just listening to Kerry, which was really helpful and insightful and we can go back to some of the questions. I can add on to some of the questions about bosses and stuff like that.

Lucy Blair Chung:

Definitely. I’ll come back. That’d be great.

Jonathan McBride:

Yeah. Picking up on the theme, it sounds like the last two speakers have been talking about, you know, this is a time for humanity first, like don’t confuse what people know with how they’re feeling about it because… And if I were going to kind of say what’s the kind of simple rule we can all follow in this time, it’d be provocative.

It might be the case that your priest, or your rabbi, or your mother, or whomever was wrong when you were a kid when they told you to treat others the way you want to be treated, which is a great way to get a self-focused kid to think about other people. But the reality in the world is that you treat people the way they are best treated or whether the way they would choose to be treated. So instead of the golden rule, it’s the platinum rule of treat people the way they want to be treated. The reality is everyone’s going through this different because they’re experiencing it based on a whole bunch of information in their lives, right? Their view of this is based on their prior experiences and set of expectations. So you have to get past that. But we’re all human so you can kind of connect to people on a human basis. And I’ll give you an example of when this didn’t work.

As you mentioned, Lucy, I was… I started a company when I was 29 with a couple of friends and that was a year and a half before a plane crashed into a building. I was 30, almost 31 at the time, they were both 31, most of our employees were older than us. I think the oldest was 60 or 62 and had quit a job paying them $1 million to come get paid $90,000 by us to join our company. We were in lower Manhattan on Broadway and Houston and had experienced September literally together in the morning before I sent everybody home, so we went through the whole morning together. And then people were restricted from coming that far South for many weeks.

So we were back in the office probably 14, 18 days later. We had to walk in and talk to these folks. We are still somewhat of a startup and they knew the world that just kind of imploded a bit and there was so much uncertainty. My two partners and I had stayed up all night debating how should we speak to them, what should we talk about? Our rule was we’d set a time limit on our debates and then we would vote; since there were three of us, we’d never had a tie. The other two guys were really kind of leaning it on we should talk about how tough this is, but how unfortunate it would be if the thing that we’ve built together also comes to it, and kind of really focus on that and get people to feel like owners.

My gut instinct, and I’ll admit it wasn’t so much stronger than theirs, so it was kind of like a 52/48 thing. It wasn’t like I was seeing the future, but I was I thinking, well, maybe we should just start with how do people feel and let that run out the clock for the first meeting. Like the first meeting be us checking them as humans and not talking about business. So we’d debated all night; I lost the vote. We went into have the conversation the two of them wanted to start, I was standing behind them. We had about 54 full-time people and we had a bunch of freelancers and stuff on the phone, about 200. We’re sitting there and I’m looking at the 54 people standing behind my partners. About two sentences into their refrain, I knew we had lost everybody. Like you could just see on their faces this look of like, are you kidding me? So I tried to step forward and get into a conversation. It was was awkward to say the least.

We didn’t talk about those, Lucy, but I was thinking about this morning when I got up, I don’t know, we had that company for six and a half more years, we eventually sold it. I don’t know if we ever totally got all of them back. I’m really not sure. I was thinking about that this morning and there’s certain people, I can tell you without naming names, and I think basically that was that for us because they were really…they’re not…they’re… Kerry’s exactly right, people are going to be scrutinized very carefully as to how they go through this experience. My favorite, regardless of politics, my favorite Michelle Obama quote is not “when they go low, we go high,” everybody loves that one, but about four months after they took the presidency, she got asked by some reporter, was the presidency pressure filled? Are you seeing a different man in your husband? And she said, really fast, “The presidency doesn’t change who you are, it reveals who you are.”

That’s what crisis does. Pressure moments reveal your character. And people know that, so they’re going to be watching very carefully to see how you behave versus just what you say. Which is why video conferencing helps a lot because you can see my physicality and I can fake my words and my tone a little bit, but it’s very hard to fake my physicality. It’s sending signals immediately as to whether or not I’m believable and authentic, which is the key.

Lucy Blair Chung:

I’m curious then because I, yes, definitely, that these moments of kind of power and pressure reveal. What is the advice that you’re giving to leaders who now have to kind of go in front of their company like you once did and hopefully not feel the way that you did and hopefully not lose their employees for the next six, six and a half years in a major way?

Jonathan McBride:

Well, there’s been really good advice given already, which is the first thing Kerry talked a little bit about, which is you ask them, which was great, in the middle of the conversation, how you doing? And I would say stopping and thinking for yourself first how you are doing and making that part of your story, and you going first as a leader. I want to be clear, leaders can be the boss or anyone else. In this moment, anyone can be on a call and switch gears for a second, say, “Hey, can we just stop for a second? I bet everybody’s feeling a lot. I want to talk a little bit about how I’m feeling and see if everybody feels the same because I feel a little isolated now.” Like tell the story, right?

Anybody can step up and model good behavior. I can tell you, as a boss, when people have done stuff like that for me and saved my butt because I didn’t realize I had started at the wrong place, I actually appreciated it. But the first thing is, remember the platinum rule, not the golden rule. Remember that everybody else is going through their own thing. It’ll prompt you to ask more questions and that’s the right thing to do.

Secondly, you have to be ready with your own answers as to how you’re feeling. Context is very different, but human emotion is consistent. You need to verbalize your emotions and how you feel. It can’t just be what you’re doing or how you’re thinking about it. Those are important. But as soon as you tell someone you feel isolated or concerned about your children or at risk, or whatever, then people can start to meet you where you are. So make sure you verbalize the emotion as well as the thoughts and the actions because that’s how humans connect. You can read all about how Pixar constructs a narrative. Then we connect through human emotions because they’re shared. They’re kind of consistent. So that would be extremely important.

I would say in terms of thinking about as a leader, if you’re trying to lead a group, definitely spend some time thinking about how you want to come out of this. For you, individually, and maybe for your team, separately, it could even be a team exercise, but when people are going back to normal at some point, some version of normal, or a new normal, and people were coming back to the office or whatever the case may be, well, what’d you want for instance your people to say about you in remembering this time? Because they’re all going to remember it, right? What would you want them or what might they all want their customers or partners to say about them, which is a good exercise? Come up with those, figure out what those three or four things are, two or three actually would be better, and write them down. Before you do a Zoom call, before you talk to anybody, before you engage anybody, just look at them and remind yourself of the things you are trying to project and you’ll be more likely to project them.

Then the last thing is really quickly mix this type of video call with strict little reminders. The way incentive theory works is when I give you a bonus or a holiday present or birthday present, you barely remember what it is because you’ve been waiting for it all year or you’ve been expecting it, so it doesn’t have the incentive effect unless it’s a lot more or a lot less than you expected.

But the research is pretty clear, that when somebody surprises somebody with something small and thoughtful, they remember it for years because it caught him off guard. It was personalized and it was actually bite sized. That is a small note saying, “How is your child doing?” But remembering the child’s name, or that they have something that makes them high risk, or the school that they went to, or whatever the case may be. So I would definitely mix up group conversations like this and starting with how people feel, which is exactly right, with kind of small bite sized things.

Lucy Blair Chung:

I like that. I love how practical that advice is. You said you wanted to touch on some of the points that I think Kerry got asked specifically. It sounded like, what do you do if you’re not the leader? You mentioned this, everyone can kind of be the boss in this moment and maybe what that looks like, but what’s your advice there if you have a leader that’s not showing up in the way that you’ve just described and kind of isn’t thinking about what they want to have been said about them? I’m curious what’s your thoughts on that

Jonathan McBride:

Yeah. One, the kind of small things are reaching out to people and touching base with them is easy to do. The volunteering on calls, things you’ve been thinking about. Or sometimes it’s easier not to sound like a know-it-all and so you can say, “Hey, I was on this amazing conversation on Zoom on Friday and the speakers mentioned these three things. Maybe we should think about that.” Right? But you can inject things into the conversation that people of goodwill will pick up and take.

To be clear, measurement on leadership is not your behavior, measurement on leadership is who follows you when they’re uncertain. That’s the actual standard of leadership and it’s not about who has the big title in the corner office. In times like this, and I think you can fact check me on this, but I think the majority of CEOs in the Fortune 500 or 1,000 were from kind of non-dominant groups like ethnicity, race, gender, et cetera, got their jobs in crisis. Because, in crisis, everything strips away. All practical kind of like behaviors are stripped away and people are just good or they’re not.

So you can definitely do that. Reaching out and modeling the behavior with the other human beings and checking in on them what you can do. Reminding them of human things like, “Hey, do you have anybody in your life who lives alone? Is that person older? Are you calling them regularly?” One thing you can do with your team is, as people come back to this, they’re going to come back to this slowly. And you could even do this now, but one of the big consulting groups turned around its culture over many year period by doing one thing, and literally it’s one thing: when teams got together for really intense engagements, they would sit and talk and everybody would fess up about what’s the one thing I need to do when I’m intensely working on a project Monday through Friday to keep me sane? Is it going and seeing my kids twice a week by picking them up from school, is it running during the noon hour, whatever it is.

Because most people are afraid to do it when everybody’s at the office working and they’re afraid they’re being judged, so they don’t do it. So what they do is have everybody put it on the table and then everybody forms a contact that says, “We’re going to make you do that.” The stories are like people taking people’s running shoes and putting it next to the elevator and everyone’s standing there and staring at them at noon until they walk out. But right now, what are the things that make you feel a part of this team? What are the important things that drive belongingness for you? Which is a different question, and then making that be real.

And then the same thing, as people come back, to help normalize again, what’s going to be important for you? Having that same set of conversations and everybody commit to help the other person do those things, and then write them down, and keep people on and call them out. As a leader, the first time you call somebody out for not doing what they’re supposed to be doing, everybody will get the point. Again, you don’t have to be running the meeting to do that.

The last thing is somebody asked about leaders saying I don’t know. This is a wonderful moment to practice not knowing, because no one knows. The mark of a good leader is not knowing everything and doing everything perfectly. People don’t trust the perfect person because they know the guy is something. What makes people care for you in narratives and in storytelling and everything else is that you’re fallible and they’re pulling for you, that you’ve been vulnerable with them, and they’re the hero in the story by choosing to follow you. So it’s actually extremely important for you to sometimes say you don’t know, or you feel a little bit scared, or you’re nervous, you’re uncomfortable. If you want people to follow you, they follow authenticity, not perfection because they don’t think perfection is real, and it’s not. So admitting that you’re infallible and that you don’t know is a really, really super important thing.

Lucy Blair Chung:

We’re getting a lot of plus ones for that, so thank you for that point. Anyone who has questions pop them in because I’m going to be pulling from all of you after this question for Jonathan. I’m curious what behaviors you’re seeing that you think will kind of stick in our new normal? Behaviors that maybe… Because you seem to sort of sit on that bleeding edge of culture and organizational design. But what have you been looking at and saying, “Actually, I think that that’s a behavior that is actually going to stay post this crisis.”?

Jonathan McBride:

I don’t. I’m a little bit pessimistic about behaviors sticking in moments like this. I’ve been through a bunch of experience. I went through the shutdown when we were in the White House and no one was there for a while, I went through 9/11 with my team, I went through the blackout with my team. I’ve been through a bunch of different scenarios that I’ve been talking to people about this exact question. Everyone’s story was the same. We went into this thing, we had to come up with all these work arounds and change behaviors and drop platforms and processes and get stuff done, and it was really kind of cool. It was actually really great and we worked better. And then we went back to normal as soon as the lights came on. Everyone had a story like that.

So my advice would be specifically on this because I don’t know what’s going to change. I mean, are we going to work better virtually? Yes. Companies are going to be much better on the back-end than they were on the front-end and having people work virtually. Are people going to be a little more comfortable with the technologies and stuff like that? Yes. But a really good thing to do as a leader or a member of a team is to suggest, “Hey, let’s keep track of a running list of things we either don’t ever want to do again because we’re doing it right now and we hate it, which is kind of fun, but then also list of things maybe we shouldn’t go back to because we found cool, interesting ways to do it.” And then plan to have a checkpoint conversation before you all fully come back to the office or engage in normally again, somebody normally.

As a leader, pick two. You don’t have to do 17 of them. If you take two of the things your team tell you they don’t want to do anymore after what they learned and you institutionalize them, people will be, “Oh, this person’s just amazing.” I want to mention that, for years now, I’ve seen when things happen in office environments, because I had been in situations where I’m on a million chat groups and I’m in everyone’s network and something’s going on and no one’s talking about it, then you see one person go, “Oh, my manager walked in and asked me if I’m okay. And then you see, “Who’s your manager? I’m going to quit. I’m going to work for him. He’s amazing.” Like there’s a kind of this full stack on effect.

You don’t have to do superhuman things, you have to surprise people a little. Right? You have to be a little better than expectations or than the mean. So that list of things you’re going to shut down, or whatever the case may be, having it be fun and something you all talk about during your meetings and people joke about, people could say out loud, “Hey, do whatever you just said, we’re not doing that ever again.” Right? Just have fun with it, but then take it seriously before you come back.

I will say that, in my experience, I have yet to both experience or talk to someone in the last couple of days where they did that. Everyone is always going back, including myself, in environments where they’ve actually had choices. You just kind of fall back into your routines and patterns.

Lucy Blair Chung:

So during this time, I mean, sort of related, I’m getting a couple of questions about, and we’ll definitely get to this later too, everyone in our remote session as well, of how do you create a healthy culture and a culture of empathy and trust in a virtual while we’re all virtual and working remotely? What are your suggestions on that?

Jonathan McBride:

I think it’s a little harder remotely, but I think humans are human. You’re just dealing with humans and the technology and remoteness is a variable. People trust people based on their sense of understanding of that person, not necessarily… The one thing I would differ with Kerry on is that I don’t think this is a moment of tolerance. This is a moment of understanding. Tolerance is I’ll deal with you for this period of time. That would probably shut off at the end when we go back to normal. Lucy, once I know that you’re someone who processes over time rather than in the moment, if I’m running a meeting where I’m going to make a decision, I’m going to call you the next day because I’m like wondering, Lucy’s going to have a really good idea the next day, let me call her before I make a decision. Right? Once people understand where people come from, it’s very hard for most people a good 10th, to lose that part. Right?

One thing I would really want to make sure, and you’re going to prompt me maybe, but I want to say it now, which is some of you are probably nervous about starting these conversations because they’re unusual for everybody in the workplace and you haven’t done it before. Here’s the thing I’ve seen work over and over and over again is admitting. Start your conversation with the individual or the group saying, “Hey, I want to talk about something right now and it’s really personal. I got to tell you, I’m a little nervous and I’m really afraid that I’m going to say something wrong or do something wrong or whatever. But I realize it’s so important to you that I’m willing to be really nervous and potentially make a mistake if you’ll just give me a little bit of a break and tell me what I do, but know that I don’t mean it.”

What you’ve done is you’ve established in the other person a belief that you’re a person with positive intent. The assumption of positive intent is the difference between someone saying something silly and stupid and I got to tell them, “Hey, you didn’t mean it, but” which is a way to approach a bad boss. “I know you didn’t mean it, but for people who might have heard this. You might want to tweak this.” The difference between that and what a jerk, they meant that for me, right? And most people don’t wake up in the morning and say, “I want to microaggress this person all day long.” That’s not how people work.

Begin your conversation with humanity and with fallibility, but also just establishing [inaudible 00:18:42] saying again, “I’m nervous and uncomfortable.” As soon as you say that everybody will be right with you because they’ve felt nervous and uncomfortable in their life. They hadn’t been the boss necessarily and they haven’t let a Zoom conversation in a pandemic, but they’ve been nervous. So once you say that, people are on your side. And then you can actually open up the conversation and they’ll give you a break and they will give you some good advice. They’ll be like, “Hey, don’t do this.”

Lucy Blair Chung:

I think the definitely would not prompt you, that’s amazing advice and I love how you validated that it’s uncomfortable and that it’s unusual while also giving quite practical, specific ways to script it. It actually perfectly segues to our next set of speakers. Jonathan, thank you truly so much. It really was an honor to be able to talk with you today. Thank you.

Jonathan McBride:

Thanks so much for inviting me. Good luck, everyone. Be well.