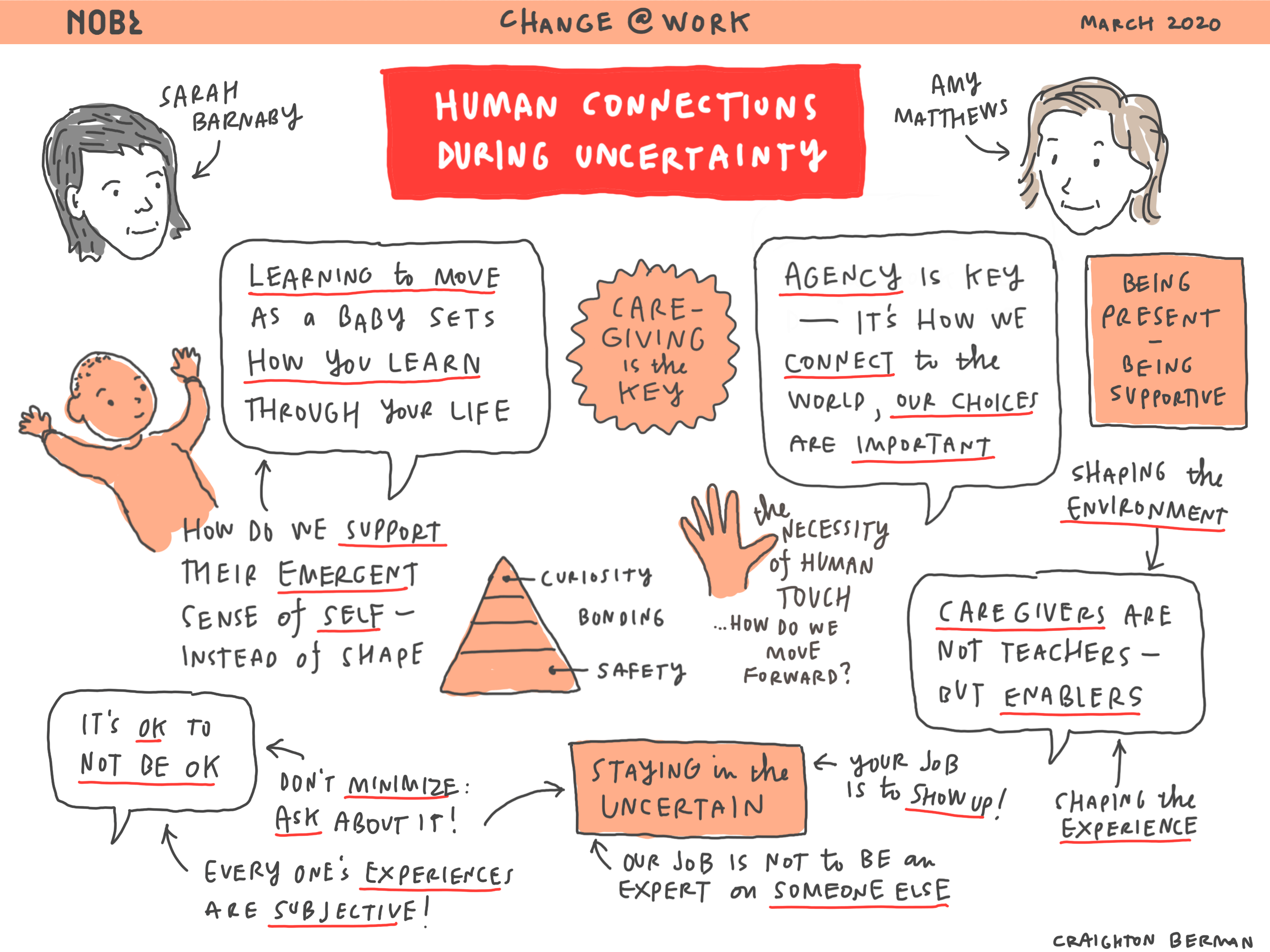

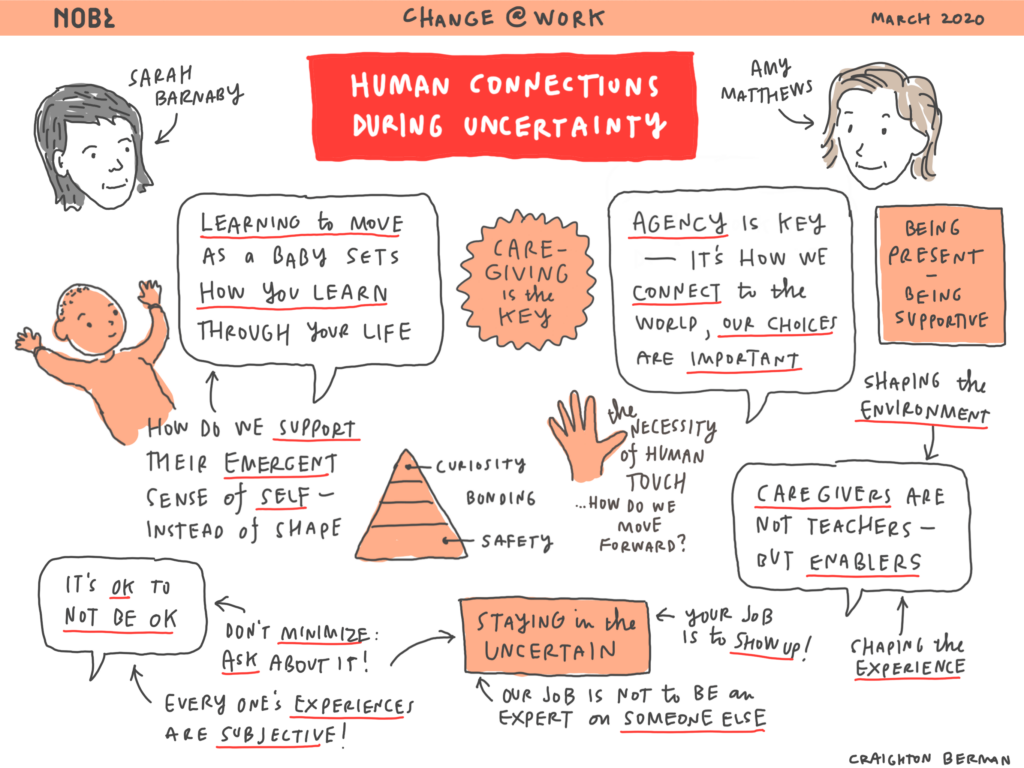

Due to “shelter at home” orders, many parents are being thrust into full-time caregiving roles, struggling to manage the demands of work and family. Sarah Barnaby and Amy Matthews, founders of Babies Project, share what they’ve learned about connecting with other people—of all ages!—and how we can support them in times of distress:

- Support others’ agency. Everyone comes into the world with a sense of agency; that is, the ability to make choices, participate, take risks and learn from their experiences. Whenever possible, give people the freedom to get involved and make their own choices.

- Don’t assume you know what others need. Everyone’s in the same situation, but not everyone is having the same experience. Your job is not to know what someone else needs or feels—after all, it’s tempting to think you know what’s best for them. Instead, your job to show up and be an expert on what you do know.

- Ask permission. Similarly, what works for you may not work for others. For some people, for instance, a hug is a welcome form of touch, while others may not feel comfortable with it.

Read the Transcript

Amy Matthews:

We created a developmental movement project, Sarah and I, which is a educational nonprofit doing business as Babies Project in New York City. We work with adults some, but in the 12 years we’ve been doing the work with babies, we do developmental movement work with babies and the caregivers, as Lucy said. When we look at developmental movement, what we’re looking at is how a baby learns to move in their first year of life. We think the importance of that is that those first experiences of moving are first experiences of learning, so learning to move is learning to learn. Those experiences then end up impacting a baby, a person’s experience through the rest of their life. Whether or not they end up being a mover, those early patterns of how they deal with experience, how they deal with new experience, how they deal with change, how they deal with challenges, those end up setting patterns that we carry with us for the rest of our life. We base the… so, we’re trying to help babies and their caregivers have this experience that let’s them grow up able to cope with change and uncertainty.

Sarah Barnaby:

I’m going to talk for a moment about agency. Agency is our first number one value, and we have Lucy to thank for helping us get really clear on that. It’s been so helpful. The way we defined agency is the ability to make choices, to take risks and to learn from our experiences. Our sense of agency also, or our definition of agency also includes an idea of participation. So, it’s not just about each person, but it’s also about how we show up in the web of connections with other people and with our environment. It includes ideas like connectivity and interdependence and acknowledgement that as we participate, we are being changed and we are having an impact. And so our choices have import. A healthy sense of agency includes participation, connectivity, interdependence. So, it’s not just about selfhood and autonomy, but also about that in relationship with others and the environment.

Sarah Barnaby:

Our sense of agency or idea of agency also includes the idea of emergence, this idea that we’re each agents in our own self creating process. We strongly believe that babies come into the world already with agency. So, agency is a given. They’re making choices from the beginning, even if their choices are not the same kinds of choices they might make when they get to be older as adults. Okay, so then agency can be a guide for us in what does that mean then about how we support a baby? Okay. It means how do we support them so that they can participate in their own emergent sense of self rather than us thinking that we need to shape them.

Amy Matthews:

So, we work with this kind of hierarchy of needs, and what we work with is safety, comfort, bonding and curiosity. The idea is that our subjective experience of safety underlies our ability to get comfortable. Our subjective experience of safety and comfort underlies our ability to bond, by which we mean receive support from other people, from the earth, from the environment. And then this experience of safety, comfort and bonding lets us get curious. So, if we can keep following that cycle through our life, then safety, comfort, bonding, curiosity keeps leading us into bigger and bigger kind of spheres of experience, and that we can keep growing in what we can hold, what we can explore, what our capacity is. But we grow through our curiosity, not by being pushed past our limit and not by being taught, actually.

We have all kinds of ways we apply this with babies, like not putting a baby into a position like sitting or standing that they can’t get into or out of, but instead looking for their… kind of being with them in their own curiosity and exploration and valuing all the different ways they do all the different things they do to get there, including falling and failing and things we would never imagine. So, our job then as caregivers, we think, is not to be a teacher, but to be with and be in relationship with the baby.

Sarah Barnaby:

Following on this idea of, well, what is our role as caregivers? One of the things we say to kind of encapsulate it is we are the baby’s environment, and that is literally and physically true when we’re holding a baby, especially a small baby, we’re their ground, we’re their surroundings. It also becomes perhaps more metaphorical as they get older. We’re not necessarily holding them so much, but we’re playing. We’re proposing a really important role in how we shape their environment and how we shape their experience of their environment, and with this idea of a little physical environment, holding, handling, we focus a lot on working with caregivers and how they handle their babies. It’s true that the handling tasks are repetitive and quite numerous through a babies’ especially first year of life, the picking up, the putting down, the changing, the handing off to somebody else, all of that.

So, these are moments when for a caregiver they might be very task oriented, but for the baby, they could be big experiences. These moments are cumulative. They’re opportunities for us to support a baby and their sense of safety and comfort and have a positive impact on their development, or we could be inadvertently, we’re assuming, interfering with their development by how we handle them. Here’s an example. So, I’m going to talk about a practical suggestion we make to caregivers of how they can bring their baby from being held in arms down to the floor. We’re suggesting that we bring a baby down onto their side rather than onto their back. Why is that? If you bring a baby down to their side, they can, at least as they become familiar with this trajectory, anticipate and literally see that the floor is coming. They have some heads up about what’s happening.

Then more and more as they develop, they can start participating in this big transition of the ground being our arms to some other ground. So, we see an older child actually reach their arms out and help themselves land into this new place, and we have lots of other examples that are playing with our ideas and principles with very practical suggestions. So, to wrap up, we’re proposing that the role of a parent is not so much about teaching and molding, but more about being a support, being in relationship, responding to needs, shaping their environment, letting them lead. Thanks.

Lucy Blair Chung:

Thank you. I think what feels really applicable too, because we were going to do a whole kind of caregiving practical session as well later. Of course, Amy and Sarah were nice enough to sort of repeat their one-on-one because we got kicked out of the main room. What felt really applicable for me was that in this time, it feels like we’re all kind of caregiving each other, and so one of the things we talked about, and I’ve definitely applied your principles beyond my baby to my friends, to my other family members who are full adults.

I think this does bring us back in a lot of ways to some of the powerlessness and uncertainty that a baby must feel in those first times. Sarah, I loved your… and I used it, I don’t know if you saw me pirate what you said, but it’s okay to not be okay. Just talk a little, because I think that’s just so broadly applicable to human relating of when you often hear a caregiver say, “It’s okay, it’s okay,” when they hear a baby crying. I think we can talk about it, same thing with a coworker, right? Who’s sort of freaking out. Just walk us through that a bit. I think that’s so applicable.

Sarah Barnaby:

We find ourselves doing a lot of reframing with caregivers and parents. One of the things we hear a lot when a baby is in some level of distress or discomfort is you’re okay or it’s okay. The way we offer a reframing is we say, “Well, on some level, your baby is not okay. Their experience is that they’re not okay.” Now, it might not be dire, but they’re communicating something about their state. So, instead of starting with you’re okay, how about something like, I hear you, tell me about it, I’m here with you. We encourage parents to find what works for them, and we’re also encouraging them to consider that if this is a small baby, they don’t understand your words and they’re picking up more intention.

But this is a time when you’re practicing your parenting philosophy so that when your baby can understand the words and they’re five years old or 25 or 40 and they come to you with something, and we’re proposing we think parents and caregivers want their people to come to them, then what’s your opening response if they’re upset? It’s not to minimize, but to say something like, “Tell me about it.”

Amy Matthews:

I think… can I add onto that a little bit?

Sarah Barnaby:

Yes, please.

Amy Matthews:

I think that then with adults, part of what we’re inviting the caregivers and what we practice ourselves a lot is the comprehending the subjectivity of everyone’s experience. I think that’s, to me, significant in a time like this, that we all might be responding really differently. One of the things that Sarah and I practice really actively with each other is not saying everyone does this or every baby does this, and every person does this. Part of what I’m seeing is just it’s such a huge response to what’s going on. One of the things I find personally frustrating is when people say, you must be feeling this. So, I think in our interactions with each other, it shows up in not assuming we’re all having the same experience. We’re all in the same situation, but we are not all having the same experience.

Lucy Blair Chung:

Another-

Amy Matthews:

Can I say one other thing?

Lucy Blair Chung:

Yes. Oh, please. This is great. Build on each other.

Sarah Barnaby:

Something underneath, something to add onto that also is we are not supposed to know what somebody else is feeling. This comes with parenting, definitely, that we don’t think that somehow maternal instinct or parental instinct or caregiving instinct is just going to kick in and we’re all ready, all of a sudden going to know how to read the cues of a baby. This applies to adults. Amy and I spent a lot of time with each other. We spent a lot of time talking and being in relationship with other of our people. We might get really good at thinking we know how they’re going to respond. But if we stay in the not knowing of really not having to know, then we find it helpful, and that came up again, something about the not knowing, but it’s also in human interaction. Yes.

Lucy Blair Chung:

I would love to hear more on that. So, practically speaking, because I was this person, and the staying in the not knowing is incredibly challenging. What do you say, to whether it’s a caregiver or each other or a leader, when the staying in the uncertainty and just being present to that feels so tremendous and just as such a struggle? Practically, where are the steps that you tell them to take in terms of just staying in that?

Amy Matthews:

One of the things that I do, because I also work a lot with teaching teachers, teaching adult educators, is to redefine what we think our job is in the world. I think a lot of people, I’ve taught yoga teachers, they teach sematic teachers, other. We think that our job is to go know what someone else needs. In terms of the kind of network theory that we look at, it is not about being an expert on someone else. When I walk in and think I know what someone else needs, it’s a kind of arrogant thing to do, and it might attempt to be understanding, but… so, if I redefine my role about being a teacher or being a human being or being a friend, and I don’t think that I’m failing at my job if I don’t know, does that make sense?

Amy Matthews:

If I think that my job is to know, then if I say I don’t know, I’m failing at my job. But if my job is to show up and to be also an expert on what I know. So, one of the things we say to parents, I’m a subject matter expert on infant developmental movement, but I’m not an expert on their baby. So, how do we work together to bring together what I know and am an expert on and what they know and are an expert on? And where are we both willing to learn? I think we all need to redefine the idea of being an expert in our field or a master or a leader or a teacher, from being the person who knows what everybody needs, to being the person who has the skills to show up and be in a relationship and not know but stay present.

Sarah Barnaby:

And also how do we support someone in their needs and their distress? And with a baby we don’t necessarily even know what the need is. We know there’s some discomfort, some distress. We think that, again, what is our role? Can we be present? Can we support them in their process rather than thinking we need to fix it?

Lucy Blair Chung:

I’m just looking at some of the questions. One of them, and I think it’s really interesting, a lot of people are seeing the parallels for leaders, and I hoped that that would be the case, so I’m really happy that everyone is seeing how much parallel there is and how important, what Sarah and Amy have to impart is right now. So, one of the questions, what are questions that you two are finding yourself tackling in this moment, and what are questions that are occurring to you that feel like they’re highly relevant to this moment, and how are you answering them with each other?

Amy Matthews:

Oh, well, we have survival questions going on. So, in our hierarchy of things, some of what we’re talking about is how we will survive. We’re a tiny nonprofit in New York paying New York rent. So, we live in that question of how we will survive also. But I think that we’re in a question about how important touch and handling is and contact is, and how to communicate about that from a distance. Luckily we’ve done a lot of online sessions already with people, like long distance coaching kind of stuff, so it’s not completely foreign to us. But that’s a question. And then also just what community online looks like, because a lot of what ends up happening in our space is moms coming together and talking to each other and getting the support of being in a group of people who are holding the same questions. I think for these redefining times, finding other people who are in the same conversation is really, really important, obviously.

Lucy Blair Chung:

Sarah, what about you? What’s coming up for you? And I love that you just brought it back to the fact that, yeah, you’re a small business and a small nonprofit in New York City, and this is really hard in many, many ways. So, yes, thank you for that. Sarah, what about you? What kinds of questions are occurring to you?

Sarah Barnaby:

Well, I’m going to pick up on where Amy was. We have a space in New York, we have this beautiful studio where we meet babies, and we’ve been thinking about ourselves as a balance of very, very local here in New York. I mean, New York is big, but we have one physical space where we meet most of the babies that we work with and their families. We’re working on some other initiatives that are more, we think of them as more global because we want these ideas to spread as big as possible. We don’t want to spread ourselves, necessarily. We don’t want to open babies projects all over the world. But how can this get more global? How can we spread it? How can we share it? Now there’s such a big question about when, if ever, we’ll be able to go back to our local space. And so what comes next?

Lucy Blair Chung:

Yeah.

Sarah Barnaby:

I mean, it’s been almost exactly three years since we started our fundraising to start our nonprofit, to secure our space and to start, and it’s been gradually building and building, and we’ve been making it up as we’ve gone along, as things change and we learn more and we find things out, and so we’re going to keep doing that. It’s bumped up a huge level.

Lucy Blair Chung:

So, interesting, this is what’s coming up in questions as well is what’s the hack for the lack of human touch right now. Amy, you mentioned it of doing this virtually, and Sarah, I know you talked about virtual sessions when we were on our prep call. What are the tips on maintaining the value and the incredible necessity of human touch when we are all in these kind of isolated circumstances?

Amy Matthews:

Well, one of the things, and this actually has to do with the question about what we’re thinking about now. One of the things I’m finding really interesting about touch as a question is that, in a way, this has been coming. I was watching a TV show the other day, and it was about a ballet dancer, and so much touch happened in these classes. Because I I teach adults touch and movement in a touch and movement training in a somatics practice, one of the things that has been coming in more and more to the way we do our training is asking before touching. So, the world used to have a lot of just, “Oh everybody loves touch, so I’m going to touch everybody and everybody will like what I offer.” And the kind of magical thinking that touch always feels good.

It is also true that touch does not help everyone. I think we sit firmly in the question of how do you ask permission of a baby before you touch them? But also when we’re engaging with adults, I’ve already been teaching, we do a lot of partnering in the work I do teaching adults. But how do you partner without touching? If someone’s full up with touch, someone doesn’t want to touch, how can you still engage in the question? And we’re asking everybody to brainstorm. I don’t know the hack. I don’t think Sarah does either though, though she might. I don’t think we’re so much about hacks, but one thing we do is, can you touch yourself, or how else can you get a soothing touch? Can water soothe you? Can weight soothe you? Or how do you get what you need and how can we be creative about it?

But also can we not assume everybody needs the same thing? So, to the person who asks how do we hack this, I would have to come back and say, “Well, what works for you? What are you missing? What are you looking for? What does touch mean to you?” Because it means so many things, and they’re not all good touch, just got to say that.

Lucy Blair Chung:

Sarah, do you have something to add to that? I want to make sure I give you space.

Sarah Barnaby:

Well, it means more words, I think, and getting more creative about how we set up maybe shared experiences. I recently did a online session with a couple preparing to have a baby. We teach a workshop in our space on touch and handling skills for people before they come with their babies so that they have something to start with. We heard so much from parents and caregivers who came in and we would share suggestions. They say, “Oh, I wish I had known that before.” So, we created this workshop and recently did an online session, and one of the experiences we sometimes do to convey what it is to hold a baby is we use water balloons. So, I asked them, get water balloons, here’s what you need to set this up. And so there’s a way that walking them through it, talking them through it, me having a water balloon, them having a water balloon, we can be in a shared experience where touch is involved without us touching each other. So, we’re going to have to get creative then.

Lucy Blair Chung:

Amy, this is-

Sarah Barnaby:

By the moments when we can come together physically.

Lucy Blair Chung:

Yeah, I couldn’t agree more on we’re going to have to get creative with it. Amy, you made the point of I would turn that back and say what works for you? That’s something that’s coming up in the questions, and I felt this right when I worked with you both, is that you really are trying to put the caregiver and the humans in the place of being empowered or helping them feel empowered. I remember that framing was important, helping them feel empowered to be able to relate.

Sarah Barnaby:

Did we lose Lucy?

Amy Matthews:

Did we lose Lucy? I wonder, can other people still hear?

Lucy Blair Chung:

Yep. I just froze for a second.

Amy Matthews:

You froze up, yep.

Lucy Blair Chung:

Sorry. I’m imagining leaders in this position of wanting to really help their employees feel empowered and wanting them to have this agentic experience and wanting them to step up in this moment, and how that can sometimes feel really mutually on both ends feel frustrating. I know I felt this when you first kind of started to show me how to care give in the ways of your philosophy, which ultimately changed for the positive the way I parent. But how do you deal with that, right? How do you deal with you’re kind of turning it back over to them, and there’s this sense of, “This is totally uncertain. I need your guidance. Tell me exactly what to do. How do you deal with that learning curve, and what do you kind of say to that? What’s the advice you give there?

Amy Matthews:

I feel like that has to do… I just read a question, the question and answer thing too about what do you do when someone really wants specifics and they’re not okay with us saying we don’t know. I think my experience of hearing Sarah talk and what I feel like I practice is that I personally have a lot of information. So, I’m like, “I can tell you a lot of details, and then I’m going to sum it up still with what’s your experience.” So, do you think there’s a role for an educator in sharing whatever our expertise is, if it’s kind of information or data that someone else doesn’t have that might be useful to them, but to then still tip it back to, so now what do you do with this that I just said? What does that mean to you, and how does it make sense to you?

One of the things I think we also do with infants, but it would be good to do with everybody is we make our suggestions, but in the end, they have to figure out what works. The caregiver has to figure out what works for them and for the baby. And so the best, best practice in the world doesn’t work if it doesn’t work. All right? So, there’s all of our advice, and then it shows up really concretely with a baby crying. We have all these ideas about how to soothe a baby, and sometimes you have to do what’s familiar. We might think what’s familiar is not helpful to their movement development or long-term orientation or whatever, but what’s familiar in that moment will be soothing, and so we just have to negotiate it moment by moment. We say, our tagline on a lot of our things is to be with, be a witness, be in relationships. The practices, I mean, in the somatics field that I’m in, the practices that we do that are about witnessing and about being with are not easy ones to do.

To be present to someone in their distress and not try to fix it but be with it, this is a practice. It’s not the absence of doing something, it’s a really very active exercise in being present and seeing what comes up in me and what my response is to someone being upset, and, yeah, how do I not fix it but be with them? I think the whole world would be served by being more at ease with being in those uncomfortable situations, because if we keep trying to fix things and smooth them over, we’re not going to get to the place where we can have some of the difficult dialogue or hold the difference in experiences that makes us have such different responses.

Lucy Blair Chung:

Yeah, I obviously couldn’t agree more on the broad application of these learnings. I think a lot of people are really resonating with how kind of specific and practical that is. I would be curious, maybe an example where you are witnessing a kind of struggle to be witness and be present and really kind of what you say to get that person kind of grounded in that moment. I think I was probably one of these before from [inaudible 00:27:05], so I kind of remember how you did it, and it was quite nuanced and it was physical. But I think it’d be interesting to hear from both of you how you deal with that, and I think it might be applicable for someone who’s dealing with a leader who really isn’t showing up and isn’t being present and the kind of advice that they might give their boss or their colleague that kind of calls them back to the moment.

Amy Matthews:

Sarah, do you have an answer to start?

Sarah Barnaby:

Well, I find myself wanting to sort of morph a comment into this, that I was coming up as you were speaking before, and part of it comes from me is coming back to agency and recognizing the other person’s agency, which is something about not fixing it for them and seeing where they’re making choices and what we’re offering. Not sure that’s specific enough, but we make our suggestions and we try to be clear, this is where we’re coming from, here’s our philosophy and our principles and the suggestions that come out of that, and it’s up to them to take it on or not to take it on. That’s part of their agency that we want to respect, and we are happy to be with them and to support them if they want to take it on. But we also have to respect if they, for whatever reason, they don’t.

Lucy Blair Chung:

We have to wrap up. I so appreciate all the engagement. Thank you all and thank you for appreciating the kind of beauty of what Sarah and Amy and the relevance have a say. Sarah, Amy, do you want to add any other thoughts before? And I’ll send right now, we have a new main room link, so I’m going to send that all to you in the chat if you wanted to join our remote work session. Then again, Amy and Sarah are joining us for another breakout, and let me just make sure I have the time right, at 12:40 PM EST. So, in just over an hour for a much more focus on the caregiving piece and the work with babies and kids. Obviously this is incredibly applicable if you’re currently home with children and when normally you aren’t. So, any last points and then we’ll head over to the other room? Thank you again both so, so much. I feel so grateful to both of you.

Amy Matthews:

Thank for the opportunity. Sarah and I spend a lot of time talking about how these ideas apply not only to babies but to the whole world. So, it’s really great to get to see all the comments and to see that other people also think this applies to everything. So, thanks to everyone for listening.

Sarah Barnaby:

Yeah, thank you so much Lucy. It was really exciting to see at the very beginning how so much of… to your intro, but also the other speakers, how these kinds of ideas are out there and people are working with them in so many different ways. Yeah, it’s exciting.

Lucy Blair Chung:

Thank you, and we’ll see you all in the main room, and Amy and Sarah, I’ll see you back in our next breakout.

Amy Matthews:

Super, thank you.

Lucy Blair Chung:

Thank you.

Amy Matthews:

Bye.