2020 has been a reckoning for many of our clients: they’re looking at their organizations and seeing strengths and flaws like never before. One client has been pleasantly surprised by how well the team is working—COVID has forced her leadership team to unite around a common purpose and make decisions without previous dithering or delay—and she wants to cement these behaviors as the new normal. At the same time, another client has seen existing silos and fiefdoms become even more entrenched as work has gone remote, causing internal progress to stall and customer outcomes to suffer.

Additionally, a few bold executives have gone beyond this: they’ve asked us how they could make a radical shift to their organization, to have it not only be a good place to work, but a force for good in the world. Some have taken a hard look at themselves and realized they were playing a role in furthering inequality, and inspired by the work of Dr. Ibram X Kendi and colleagues, are seeking ways to become anti-racist organizations. Others want to go beyond the lip-service of lofty purpose statements and challenge the system itself with a new business model, a new approach to ways of working, and a new way to measure their success. In one founder’s words, “How can my company confront a world that’s unjust, unequal, and quickly unraveling?”

Regardless of your vision for the future of your organization, the underlying question is one of resilience: how do we create organizations that can withstand uncertainty, ones that don’t just survive, but adapt to a rapidly evolving future? With all of this self-reflection, a single phrase has gained intense popularity.

“Build back better.”

The Beginnings of Building Back Better

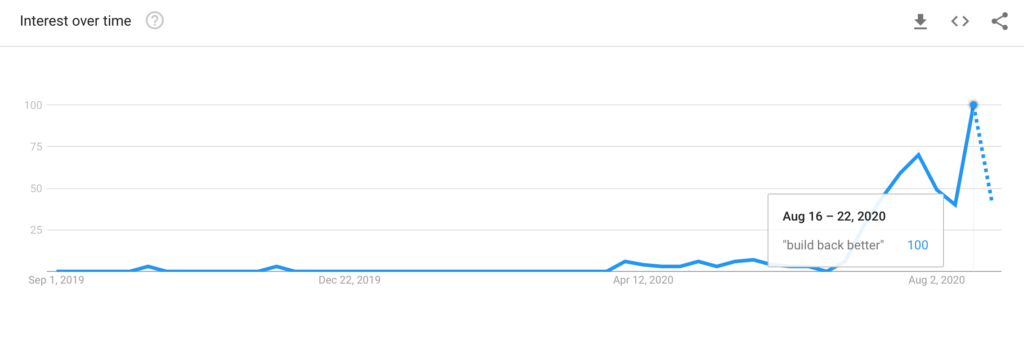

According to Google Trends, “build back better” as a term has seen a dramatic increase in search volume since June. Partly, this is the result of one of the candidates for U.S. President adopting the phrase as their economic platform. But it’s not just politicians using the phrase. Fast Company, the UN, and the World Economic Forum (among others) are calling on businesses to “build back better” in response to the pandemic.

The phrase first came to prominence in response to the devastating 2004 earthquake and resulting tsunami in Indonesia which left 170,000 dead in Indonesia alone. Aid responders realized that when rebuilding infrastructure, it should not just replace structures, but rather, be more resilient to future earthquakes. Not only that, there was a responsibility to address the societal conditions which themselves could foster or inhibit resilience. The phrase stuck, and the UN adopted as part of their general approach to disaster recovery in 2015. And while definitions have differed when proposals were being developed, guidelines have included concepts such as:

- Preparedness for future disasters

- Empowering people to direct their own recovery

- Fairness and equity

- Decentralization and local empowerment

- Enabling entrepreneurialism

- Increased coordination and collaboration of local agencies

For non-governmental organizations, AKA the rest of us, the task at hand is to translate what exactly “better” means if we intend to “build back better.” Left undefined, “better” can remain slippery or outright obfuscating. In advertising, as an example, “better” is a well known “weasel word.” It allows you to say something and yet nothing at the same time. It is a vague promise, one that conveniently can’t be held to account. Therefore, if we intend to build back better, we should first define “better”–for those we are making the commitment to and for ourselves, so that we can actually track our progress toward a worthy, yet challenging goal.

A New Model for Resilient Organizations

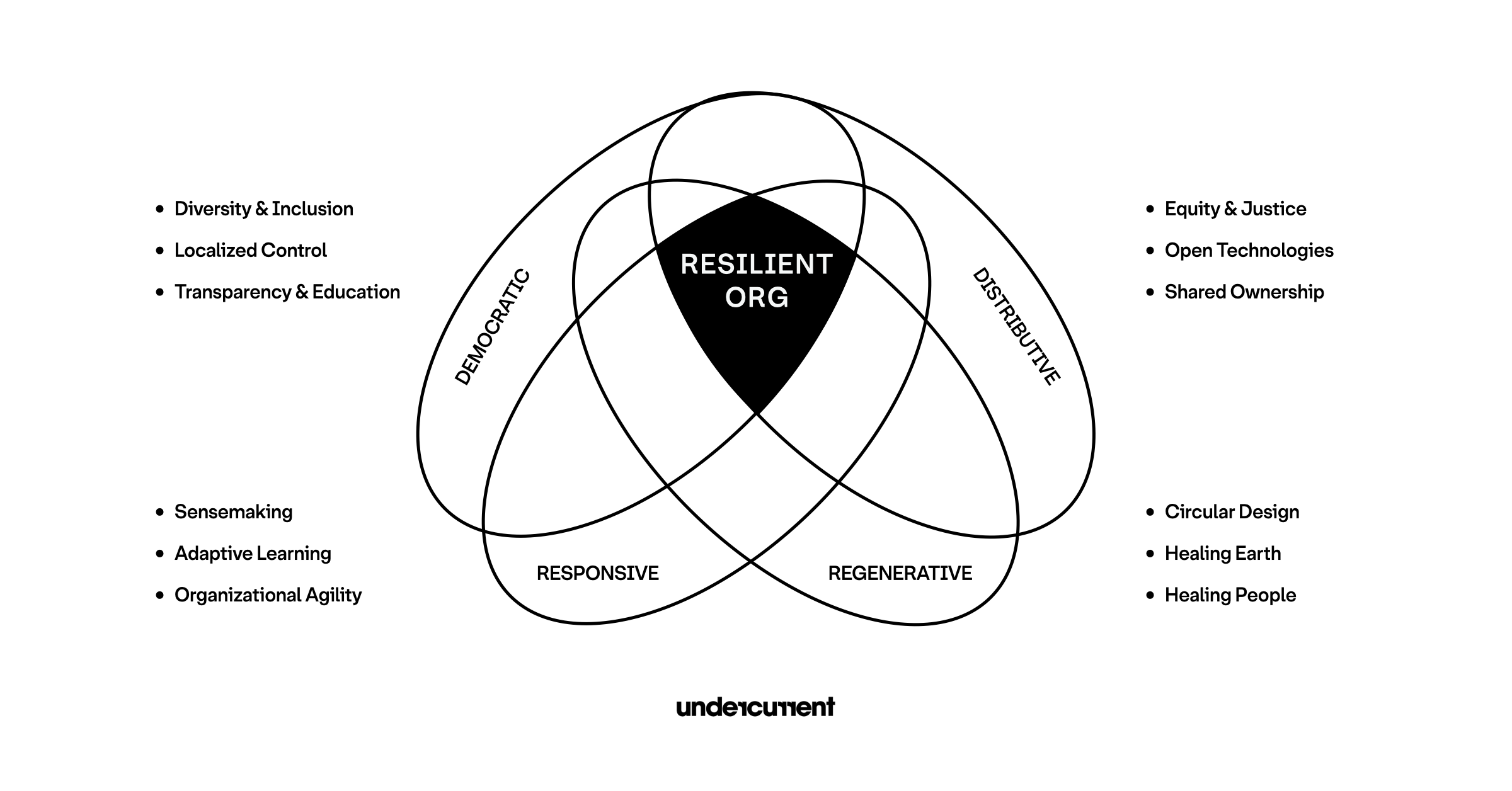

In February 2020, only days before COVID would come to reshape reality here in the U.S., we at NOBL worked with our partner Undercurrent (informed and inspired by their incredible network of subject matter experts) to develop a model for organizational resilience extending from four emerging movements in the future(s) of work. After all, the original intent of the phrase “build back better” was to leave communities more resilient for the future. Together, we designed an initial playing field for organizations looking to “build back better” with clarity and commitment. The message of the model is not to say you must do everything, but instead, pick key areas to explore and traits to experiment with based on your ambitions and environment.

Our model for Organizational Resilience includes four overlapping areas to play:

- Democratic organizations

- Distributive organizations

- Regenerative organizations

- Responsive organizations

Democratic organizations, broadly defined, invite their workers and communities to have a say on matters which affect them most. Examples include W.L Gore and Associates in the U.S., Mondragon in Spain, and Semco in Brazil. Organizations here are diverse and can be plotted across a spectrum, from active listening all the way to direct control. Research indicates that democratic organizations may benefit from increased productivity, employee engagement and satisfaction, and organizational longevity.

Traits of a democratic organization may include:

- Diversity and inclusion: History shows us that democracy, itself, is a project of ever expanding the communities and voices it includes in the decision-making process. Democratic organizations focus on accruing a diversity of voices, ensuring individual psychological safety, and enforcing inclusion in relevant decisions.

- Localized control: Democratic organizations want to ensure that people have a say in the decisions which will impact them greatest. This is rarely about giving a say to everyone in the organization on every topic, and much more about localizing decision-making to those both most impacted and most “in-the-know” about the conditions relevant to the decision. At Semco, for example, they accomplish this localized control by keeping teams small and hierarchy lean.

- Transparency and education: In order for workers and communities to make informed decisions, they need information to be transparent and readily accessible. They also need their team members to possess an understanding of the full organizational system so that they can comprehend the wider implications of their decisions. Remember, for every piece of information you make transparent, you must also ensure those with that information can understand and use it.

Distributive organizations, broadly defined, reward their workers more equitably for their efforts and distribute more of what was once considered private assets to their communities. Examples include Publix Super Markets, Google, Ben & Jerry’s, Tesla, Recology, and Brookshire Brothers. Again, the spectrum here is wide as some of these organizations are fully worker owned or they simply make elements of the organization more freely available to the community. Research indicates that distributive organizations may benefit from increased profitability and resilience.

Traits of a distributive organization may include:

- Equity and justice: A distributive organization should, at its core, include a belief in fair and just rewards. A distributive organization should place attention and commit to continuous improvement in overall fairness: particularly in how employees and communities are treated, compensated, and given access to opportunity and development. Moreover, distributive organizations must root out the systemic causes of inequity and discrimination (in all forms) through meaningful self-reflection, corrective action, and even external lobbying and influence.

- Open technologies: Distributive organizations recognize an increased strategic benefit (and even moral imperative) in making their internal technologies, once a highly guarded asset, freely available to their competitors and the public. For example, in 2014 Tesla flipped all of their patents to open source with the stated hope of developing a cross-industry technology platform that could accelerate the advent of sustainable transportation and reduce carbon emissions.

- Shared ownership: Rising from equity and justice, distributive organizations may also create opportunities for employee ownership. Moves to direct employee ownership are gaining in popularity in industries like craft brewing, where hard work, fairness, and independence are often core values. Further out, some organizations and researchers are experimenting with blockchain technologies to reward worker and stakeholder participation while also decentralizing management functions.

Regenerative organizations, broadly defined, respect the natural limits of their workers, communities, and the ecosystems in which they operate in order to serve all life. Examples include Patagonia, Unilever, Schneider Electric, Levi Strauss, and Method. This movement is a product of the larger environmental movement, advanced sustainability practices (including regenerative agriculture), the UN’s Sustainable Development Goals, and 21st century economics. Proponents of regenerative organizations argue that not only is the approach essential in a world of fixed resources, but its practices produce higher shareholder returns and greater benefits for all of society.

Traits of a regenerative organization may include:

- Circular design: Taken from the concept of the circular economy, regenerative organizations strive to design and develop products that have no beginning or end to their product lifecycle and therefore produce fewer waste products or pollution. For example, recognizing that two of the largest users of virgin rubber are shoe and tire manufacturers, Timberland has partnered with Omni United to produce a line of tires that can be recycled into the soles of new Timberland boots.

- Healing earth: If the goal of circular design is to do no harm, many regenerative organizations aim to go further by actively restoring the landscape and life represented in the ecosystem surrounding their operations. In his TED talk, chef Dan Barber shares how in Spain he found a delicious fish and radical approach to sustainability.

- Healing people: Regenerative organizations believe that organizations should support both the physical and emotional health of their workers and communities. This begins with basic workplace safety (psychological safety included) but goes far beyond this to include services such as coaching, counseling, caregiving, mindfulness, rehabilitation, and community development (among others). These organizations also believe that work can be a restorative force. For example, Nehemiah Manufacturing, based in Cincinnati, actively hires and supports workers with criminal backgrounds and sees not only lives transformed but dramatically lower turnover rates than the industry average.

Responsive organizations, broadly defined, learn from and nimbly adapt to their customers and communities. Examples include Zara, Spotify, Airbnb, Netflix, Microsoft, and Amazon. This movement originated from the software industry, with roots tracing directly back to the Agile Manifesto, but has since expanded as a shared mindset and approach to work across other industries. Proponents of responsive organizations argue that research shows it delivers faster response times to market changes, higher customer satisfaction, and improved efficiency.

Traits of a responsive organization may include:

- Sensemaking: In an organizational setting, sensemaking is the process in which actionable meaning can be ascribed to events and needs by identifying patterns among weak and emerging signals. Responsive organizations need to make adequate sense of the world in order to better serve their customers and communities. Ultimately, sensemaking is a combination of activities which include listening (which begins with developing an architecture for listening), probing (via rapid experimentation), retrospecting, and finally a dispassionate comparison to what the organization has learned previously.

- Adaptive learning: In a responsive organization, unlike in traditional management theory, “learning” as a muscle is not meant to produce an ever-calcifying set of “best practices” or “insights.” Loosely borrowing from Bayesian logic, learning here is a process of collecting assumptions about the world based on previous experience, reflecting on new information gained through sensemaking, and ultimately making a prediction (recognizing uncertainty) about future outcomes. For example, let’s say in the past our customers have tended to value choice and convenience even at the cost of affordability, yet during COVID we have signs that their purchasing power is limited, what odds of success then would we give a new premium product line? And what early events and outcomes could signal a need to rethink our approach overall?

- Organizational agility: Responsive organizations compete through speed and customer intelligence. Consumer intelligence is accomplished through sensemaking and learning, speed is accomplished through an obsession with operational agility. This obsession often includes adopting a customer-first mindset, continuous improvement practices, network-based team structures (often interdisciplinary), and accelerated decision-making.

Again, we’re not saying that your organization must embody all of these principles at once, or that your organization isn’t “better” because it doesn’t address one of these categories. Instead, think of democratic, regenerative, and distributive, and responsive as options for steering your organization towards becoming a more resilient organization—that is, one that can adapt and thrive in the face of the next swan, whether it’s black or green.

The First Steps Towards Becoming “Better”

While models can help us understand where organizations can evolve depending on their strengths and skills, it’s not enough: leaders must take action. As the World Economic Forum notes, “building back better is about much more than corporate social responsibility: it is about truly aligning markets with the natural, social and economic systems on which they depend.” To get started:

- Define better. Whether you simply want to reclaim what you lost to COVID, retain what you’ve gained, develop more resilience into your organization, or be a force for broader good, don’t allow whatever promise you make to be “better” to be hollow or amorphous. Align on what “better” specifically looks like for your team or organization, and how you’ll achieve that. Be wary of “___- washing” (whether that’s greenwashing, wokewashing, or other) which focuses more on making a statement than following through with results.

- Ask “better for whom?” Whose needs take priority? Who are we centering around? Is it the board? Staff or customers? The communities we impact? For those with power/privilege or for the marginalized and underestimated? Keep in mind, the desires of different groups may not always align: donors built “safer” houses for tsunami survivors in Thailand, but not ones that addressed the “needs, livelihoods, and lifestyle of the Moken people.”

- Provide context for the team. Any change—even one for the best—can feel like loss. Plan how to communicate why we want to be better, and why it’s important that we do so at this time.

- Remember “better” is a process. No one expects perfection. What’s important is the process; the dedication to constantly and consistently make small changes that move you towards your definition of better.

- Be humane. At the same time that we’re trying to make things better, we’re also trying to survive a global pandemic, political unrest, and more. Be conscious of how much change your organization can metabolize, and find ways to build in slack so you can commit to making change over the long haul.