Hybrid work means scheduling sounds like one of those dreaded word problems: if Nick only comes in Tuesdays and Thursdays, and Danielle works from home Monday and Tuesday afternoons the first and third week of the month, but Ryan lives in another state, when and where should you hold the next project brainstorm?

Not to mention, with more teams thinking of hybrid work for the long term, individuals and organizations will put a premium on their time: exactly what activities are so important that they warrant a commute or travel? And that’s if people are willing to come back at all: a third of professionals are willing to quit if they’re forced to come back to the office full-time. Our prediction: there’s a storm coming. Organizations were surprised to find that moving to remote work was easy, even instantaneous. But coping with a new normal of hybrid work will be far messier and will require months of experimentation and fine-tuning.

To make matters more complicated, many of the key decisions will come down to the people in power, and if a recent study is any indication, this could be divisive: “while 83 percent of CEOs want employees to return in person, only 10 percent of employees want to come back full time.” So as you develop your organization’s plan for hybrid working, first reflect on what your leaders truly believe about work and teams. You may find it helpful to keep in mind social psychologist Douglas McGregor’s two approaches to management:

- Theory X is authoritarian: managers believe that people are unmotivated and dislike work, so they need rewards, punishments, and micro-management to get the job done.

- Theory Y is participatory: managers believe that people naturally want to take ownership of their tasks, resulting in a more collaborative style of working.

Of course every organization needs some balance—too much control is demotivating, while not enough alignment is ineffective—but either way, your leaders’ biases will impact how you implement hybrid work. To keep decisions as objective as possible, leaders should evaluate what types of work must take place in-person, and what can be accomplished remotely. We need to start thinking of the office as just another tool we use to get work done, one that should only be selected when it makes sense given the kind of work required:

- Does the task require physical equipment or a manual transaction? While you’ve hopefully given your team a budget for their work-from-home set up, and adopted the right tools to make remote work more effective, there may be some tasks that require specialized equipment or customer interactions that can only be found in the office or retail setting. For these reasons, the whole conversation around hybrid work is largely focused on more privileged “knowledge workers” in the economy. Like we shared in our State of Work report, the pandemic has exacerbated inequities at work.

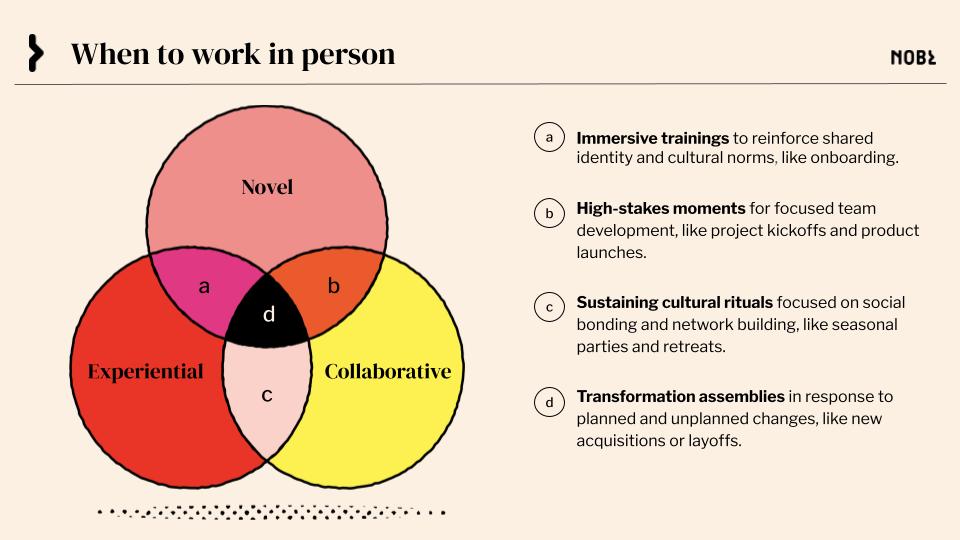

- For workers who don’t require specialized equipment or physical infrastructure, we believe in-person (either in an office or offsite venue) may still be beneficial when work is a combination of two or more of the following conditions: novel (the task or challenge is new; there may not be an established process), experiential (an immersive experience can possibly be more effective), and/or collaborative (when tasks require sustained synchronous participation among a group). Some examples:

- Immersive trainings: when individuals may benefit from immersive learning experiences outside of the home; could include the first days of on-boarding to reinforce shared identity and cultural norms

- High-stakes teaming moments: when teams may benefit from physical proximity and focused team development around crucial project milestones (e.g. project kickoffs, product launches, etc.)

- Sustaining cultural rituals: when teams, divisions, or the whole organization may benefit from in-person gatherings focused primarily on social bonding and network building (e.g. seasonal parties, retreats, etc.)

- Change and transformation assemblies: when teams, divisions, or the whole organization may benefit from in-person gatherings in response to planned and unplanned changes (e.g. addressing layoffs, strategic pivots, integrating new acquisitions, etc.)

Finally, we offer one simple rule of thumb: if you’re all going back to the office to primarily stare at individual screens, you probably don’t have to be in the office.