If you rewind the tape on many dysfunctional teams, you find that the inciting incident was a simple case of unstated expectations and norms. Someone didn’t know not to hit reply-all with their question (which inadvertently read like criticism). Or someone didn’t know they couldn’t make the decision for themselves, so they took initiative but stepped on toes. A conflict then ensued, but only through glancing blows and passive aggression. Instead of two people slowing down to address what happened, their allies rallied and camps formed on the team around each person, making the conflict personal. Now in the present, the conflict has become intractable and trust is nonexistent because the team has cemented the issue in terms of unbridgeable character flaws: She did this because she’s that kind of person and I’m not that kind of person so we’ll never see eye to eye. Little can be done now to create change without requiring a change in personnel, meanwhile, the work of the team has floundered or come to a dead stop.

Unspoken rules and unconscious roles are the icebergs in the dark waiting to sink new teams. And in this age of hybrid work, where new teams are formed quickly and often never meet in person, talk of expectations is quickly crowded out by discussions of goals, deadlines, logistics, and poor calendar management. As we’ve been running team retrospectives with our clients, we’ve noticed that in this new era of work, teams have far fewer shared agreements about what they owe to each other and what good teamwork looks like. This makes shared accountability, especially at a peer level, almost impossible and ensures conflicts will rapidly fester into cultural schisms.

Unspoken rules and unconscious roles are the icebergs in the dark waiting to sink new teams.

The organizational theory of sociotechnical systems tells us that any change in technology requires a corresponding change in culture (and vice versa). As we discussed in our article on trust, hybrid or fully remote teams need different cultural tools to make their use of technology more effective. One tool is swift trust: a theory of trust proposed in the earliest days of virtual teams that asks teams to extend large amounts of trust to each other right from the start and verify that trust is still safe to extend as time goes on (versus trust developing slowly over time). When we work with new hybrid teams, we often review the concept of swift trust and ask folks if they can take the leap together. We also introduce the concept of ‘what we owe to each other’ or Initial Commitments, to establish a baseline of accountability for a new team. These are 7 initial responsibilities that the team can amend over time and make their own, and creates a checklist for the team to reflect on after the first 60-days of working together. The following is our standard set of Initial Commitments to get new teams started.

I will be accountable for:

- Delivering what I promise: I will take my commitments (starting with these) seriously, manage my tasks and time effectively, and fulfill my obligations to the team. If something outside of my control threatens one of my commitments, I will communicate quickly and openly with the team.

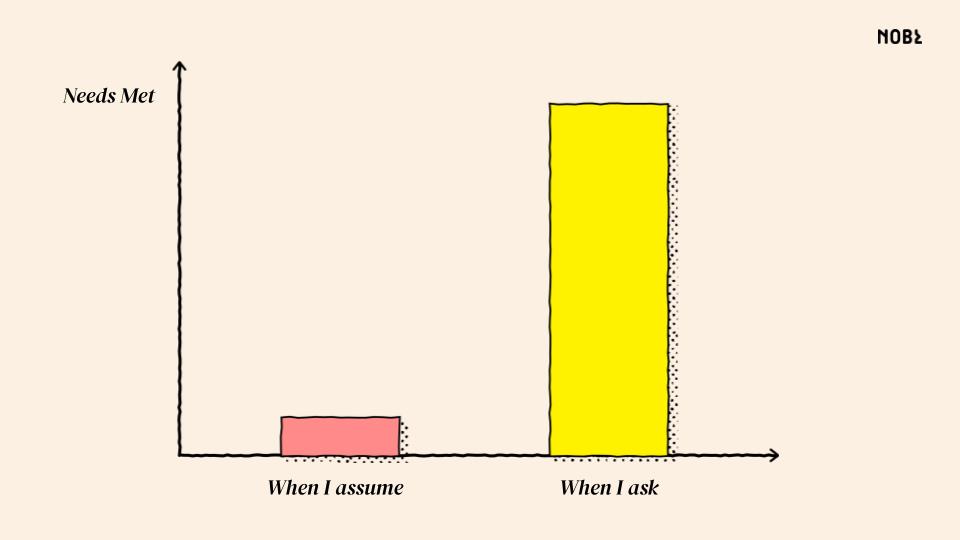

- Speaking up when things are unclear: When my role, my projects, the rules we follow, the language we use, or anything else is ambiguous or confusing to the point that the way forward is unclear, I will promptly ask the team for help and clarification. I will not wait for clarity to come on its own.

- Welcoming feedback from others: I will make it safe for others to give me feedback (and for myself to receive that feedback) by explicitly asking others for specific feedback about my work. I will seek feedback not just from my direct manager, but from peers and partners, and will seek out and learn from challenging feedback as well.

- Practicing respectful dissent: When I believe I may disagree, I will voice that disagreement with humility (treating others as equals and the problem free from superiority) and helpfulness (with the intent to help the team grow and succeed). Win or lose, I will also move forward with humility and helpfulness.

- Demonstrating personal improvement: I will embrace a growth mindset and will work to improve upon the skills and abilities that the team needs from me, especially based on their feedback. I will take ownership of my own craft and development.

- Calling others into accountability: When someone on the team fails both in a commitment to the team and in taking personal accountability, I will speak directly to them to address their behavior, their impact, and changes needed moving forward. I will do so with the the intent to help them change their behavior and help the team succeed, so I will refrain from using shame or focusing on their character. If the behavior continues, I will call the team together to discuss solutions.

- Recognizing and rewarding others: I will recognize and reward others for their positive contributions and for keeping their commitments to the team (including dissent and holding others/me accountable). Based on their preferences, I may do so publicly or privately.

As you can see, these are written to be personal accountabilities first and foremost. We want individuals, before attending a team retrospective for example, to spend a half-hour conducting a personal inventory to determine if they are showing up as a productive member of the team: Did I deliver what I promised? Did I speak up when things were unclear? Did I ask for feedback? Did I voice my concerns by practicing respectful dissent? Have I shown personal growth? Did I hold others accountable? Have I recognized when others honored their commitments? If each member of the team holds themselves to the same high level of accountability, the team can focus their improvement efforts on ever more substantial innovations and become a truly high-performing team.

Together, swift trust and these initial commitments create a safe playing field for teamwork in new hybrid or fully remote teams. Swift trust creates the ability to take risks together and the team’s initial commitments ensure that simple misunderstandings don’t derail that ability, preserving it for when true leaps are required of the team: say, when someone has a new idea to pitch, a new way of doing things to try, or a new relationship to make.