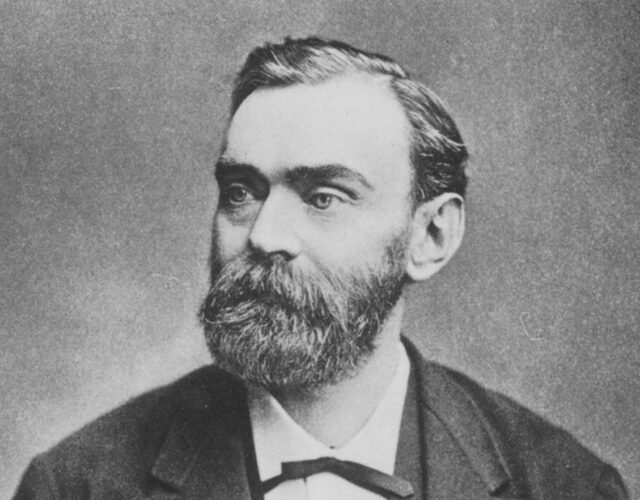

The year was 1888. A French newspaper ran an obituary for Dr. Alfred Nobel, a man of enormous wealth and reputation – namely for the invention of dynamite.

“Dr. Alfred Nobel, who became rich by finding ways to kill more people faster than ever before, died yesterday.”

The man reading the obituary was Dr. Alfred Nobel, himself.

The paper confused Alfred for his brother Ludvig, who had just died. Thanks to this error, Alfred Nobel got a rare opportunity to see how the world would portray his life and remember his legacy.

Six years later, when Alfred’s life did end, his heirs and peers were shocked to find that, in his revised final will and testament, he had dedicated his vast wealth to the creation of a new prize for humanity. It sought to reward achievement across the sciences and liberal arts that were in pursuit of “the greatest benefit on mankind.”

This is a photo of McKay Everett. This photo was taken on the day he was abducted from his home. He was 12 years old. He was my closest friend. I haven’t had one as close since.

I remember sitting with two agents from the FBI, answering questions about my friend. Where we played around our houses, the names of our other friends, and what my friend would do if he were ever upset – it seemed he had gone missing the day before and no one had heard from him. I swore up and down that I wasn’t hiding him somewhere and that we weren’t playing some elaborate trick on everyone.

The next day I followed those agents and other law enforcement officials through the pine woods where we played – I showed them where we built forts, where we staged epic battles, and where camped out under the stars. The whole time, I walked alongside cadaver dogs that were brought in to help find his scent.

Weeks later and hundreds of miles away, his body was found in a Louisiana swamp.

We were the same in so many ways, he and I. And yet, I’ve had over seven-thousand more mornings than he was given. Have I done enough with that time?

Have I accomplished enough for the both of us?

When I was six years old, I started going to work with my father in downtown Houston. He’d show me the tall glass office buildings he was in the process of erecting or the highways he was paving. Once, he walked me several dark miles in drainage tunnels he had built under the city. He didn’t own any of these things. He didn’t own the skyscraper, the highway, or the tunnels under Houston, but they were his. They were things he built for others but also built for himself. They are achievements which will certainly outlast him, and likely me, too.

Thankfully, my father is still alive. But his accomplishments, his monuments, weigh on me with their perpetuity. In my career so far, I’ve struggled to build anything that offers others the respite his buildings give, have the permanence of concrete and steel, or have the same clear purpose as the highway snaking across an urban landscape.

Like most of my generation, my career has had all the calm and consistency of a pinball.

I grew up selling sodas on the golf course behind our house (illegally, I might add), assembling computers, designing logos, and building websites. Before I finished college, I had already been a Flash developer, Coldfusion programmer (running technology at a venture backed startup), print designer, journalist, editor, project manager, and for a while I operated an eBay business that sold everything from guitars to Gucci underwear. After college, I got incredibly lucky and found myself (with a handful of others) in a position to tell Fortune 500 CEOs what to think about the web. What started as marketing and communications advice began bleeding into operations, manufacturing, distribution, etc. I had a knack for understanding how businesses work and how culture forms, far more than I ever did for design or engineering. But I wasn’t satisfied.

I spent a few years in advertising, where I tried to convince clients to stop putting billboards and commercial breaks on the web, and instead invent new products and services. I had a few wins, but in case you haven’t noticed by the banners and pre-rolls around your favorite content, I mostly failed.

I wasn’t satisfied, so I went back to consulting as a Partner in a New York based firm.

Two weeks ago I left that job, too. I just wasn’t satisfied.

I’m almost 32 years old now. I think I have to be honest with myself that it hasn’t necessarily been the industries or the companies I’ve worked for that have left me unsatisfied.

Clearly, it’s me.

To me, work isn’t a place you go. Work is a legacy you leave behind.

And because of that idea, I can’t seem to stay at a job.

I never heard a single person use the word ‘legacy’ during my time in advertising. I did, however, count a handful of conversations during my last week on the job where people mentioned the careers and dreams they wanted to quit advertising to pursue. That doesn’t mean folks in advertising don’t think about legacy or don’t pursue it while on the job, but I personally saw or felt very little evidence of it. My colleagues worked incredibly long hours and worked incredibly hard, but I never felt like we were doing these things for some purpose beyond ourselves or the profit margins of our holding company.

“Remembering that I’ll be dead soon is the most important tool I’ve ever encountered to help me make the big choices in life. Almost everything — all external expectations, all pride, all fear of embarrassment or failure — these things just fall away in the face of death, leaving only what is truly important. Remembering that you are going to die is the best way I know to avoid the trap of thinking you have something to lose. You are already naked. There is no reason not to follow your heart.”

– Steve Jobs

In consulting, legacy is always attached to ‘the firm’ and rarely to the client. The industry is famous for astronomical prices, repurposed work, impotent strategies, and catastrophic advisement. McKinsey can be the brand that built Enron, the brand that steered SwissAir, Kmart, and General Motors into bankruptcy, and the brand that advised All State to save money by paying fewer of its clients’ insurance claims – and STILL be the brand every new consultant wants to work for.

About a month ago, I realized that the meaning I was looking for in work couldn’t be found in an existing organization. Whether I was just being unreasonable, pompous, or worse, a ‘millennial,’ it was time to strike out and try to build the thing I’ve spent my career searching for.

And so, as of today, that’s exactly what myself and a few colleagues have set out to do.

For McKay, I want to build an organization that can partner with the largest companies on the planet to create an exponentially positive impact for the world. I’m looking for clients ready to do their best work and I’m excited to do my best work in return (and so are my Partners). I want to create an organization with a long term vision. One that can fulfill my life’s work.

For everyone I’ve ever worked alongside, I want to create an organization built on transparency and control. We’ll operate as a worker’s collective, where every employee is considered a member with equal voting rights and equal transparency into the business. I’m convinced this will be better for both our clients and ourselves. Clients will get motivated and experienced operators, not just consultants. We’ll get dedicated people who can continue to grow within the organization – rather than having to be pinballs.

For my father, I want to build an organization that gives everyone, both employees and clients, the opportunity to realize their own legacy, one that could possibly outlast themselves.

For Dr. Alfred Nobel, who this month is celebrated as his Prizes are handed out to the best among us, I’ve decided to name this new organization ‘NOBL’ as a constant reminder to ourselves what we’ve set out to do.

I have no doubt that this will be difficult. Perhaps impossible.

But I think that’s the only way anyone ever begins to build their legacy.