For confident leaders, change is an opportunity. Shifts, whether in the market or in the organization itself, create new possibilities to be explored. Of course, with new possibilities comes the need for decision-making and action. Each new change demands a confident response, whether to embrace, reject, or ignore the change, and the wisdom of that response may deliver a windfall or catastrophic loss.

But confidence has to be earned, otherwise it’s just hubris (or even delusion). Leaders have to be able to identify a change and take action without their own biases, emotions, or personal preferences—their blind spots—overriding their strategic sensibilities and their ability to learn from new experiences. Yet, falling victim to one’s own blind spots is something that happens to even seasoned and celebrated leaders.

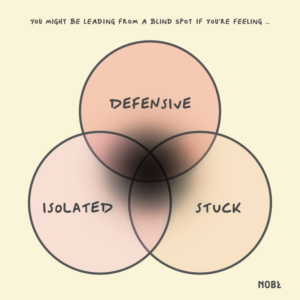

As defined by Dr. Karen Blakeley in “Leadership Blind Spots and What to Do about Them,” a blind spot is “a regular tendency to repress, distort, dismiss or fail to notice information, views or ideas in a particular area that results in an individual failing to learn, change or grow in response to changes in that area.”

Take remote work, for example. In 2020, remote work suddenly became the norm for many knowledge workers, and now that they’ve experienced it, they continue to prefer some variation on hybrid work. For leaders, remote work offers positives (e.g., talent acquisition and retention) and negatives (e.g., talent development and visibility). Deciding whether your organization continues to embrace remote work and to what degree is a strategic question, yet so many statements from prominent leaders on the matter have been saturated with loss, derision, and threat:

- Elon Musk suggested that remote workers are just “pretending to work” and has ordered his staff back to the office

- Catherine Merrill, the chief executive of Washingtonian Media, advised companies to not consider their remote workers full employees and offer them only contractor status for not participating in office-related cultural duties (like celebrating birthdays)

- WeWork CEO Sandeep Mathrani said that only the least engaged employees want to work remotely

- Netflix CEO Reed Hastings called remote work “a pure negative”

Each of these statements, and the dozens just like them, are penned from a blind spot and are patently bad takes. If the leader does turn out to eventually be right for their own organization, it will be by sheer coincidence, not strategic insight.

Given that remote work isn’t the only complicated change that leaders are grappling with right now (see also: inflation), and that blind spots are always with us as leaders, it’s imperative that we come to understand how blind spots develop, and how to overcome them in our decision-making.

Watch Out: Leaders Are Uniquely Susceptible to Blind Spots

While everyone has blind spots, several factors make leaders more susceptible:

- Prior success. Typically, leaders are in the position they’re in because they’ve been right before. It’s intuitive, and easy, to repeat what’s worked in the past, but it may also be irrelevant: one study found that leaders’ assessments of their markets can be 10 years out of date. Leaders may over-rely on what’s worked before, or assume changes they don’t understand are what David Solomon, CEO of Goldman Sachs, called remote work: “an aberration.”

- Higher stakes. Leaders are paid to be right and to deliver results quickly. Most leaders feel they have little room for taking time to understand, and almost no space to say, “I don’t know.” After all, if you’re wrong or lost, why should other people follow you?

- Commitment to their vision. Leaders are called on to paint a vision for the future, and a vision will always be slightly rosier than the current reality of the organization. The critical feedback they receive in response is difficult to parse: are folks disagreeing with what’s possible, with what’s desirable, or just with any change to how things are done? Often, when leaders are unable to discern valid from invalid criticism, they simply throw out all feedback and carry on undeterred.

- Isolation. Leaders surround themselves with people who help them get things done; people who also may protect them from discomfort and dissenting opinions. And the higher one goes within an organization, the fewer colleagues there are to discuss difficult issues with. As a result, leaders are exposed to less information and feedback.

How to Overcome Blind Spots

Blind spots are a part of the human condition: you’ll never have all the information, or remove every bias, to make the perfect decision every time. But as leaders, it’s our responsibility to continuously seek out and remove our blind spots. If we don’t—if we’re unwilling to learn and change behaviors—we’ll make worse decisions, and our organizations, and people in them, will suffer.

The good news is that you can implement some regular habits to continuously challenge and expand your mental models, and create opportunities to learn and change your behavior. Whether you’re making a big call right now, or thinking about an upcoming change, try one of the following practices:

- Pay attention. Remember, the first part of the definition of a blind spot is “a regular tendency… to fail to notice information.” Everyone notices different information or cues, so widen your scope and look for what you may be missing. The best way to do this is to expose yourself to people you don’t usually talk to. Go talk to stakeholders, especially employees and customers. Take a gemba walk to see what your employees are experiencing and/or invest more holistically in a culture of listening. In particular, be willing to listen to people you dislike. Then, review the information you’ve collected: what’s most important right now?

- Regulate your emotions. As you collect new information and go through different experiences, it’s highly likely that you will experience a variety of emotions. Maybe you’ll be frustrated that people on the front-lines don’t seem to understand your vision, or upset that a certain middle manager is cynical about the proposed changes, blocking ongoing change. These emotional responses are referred to as “hot cognition” and can lead to us acting defensive, or lashing out at others. On the other hand, “cold cognition” suppresses emotions. Most people would rather achieve their goals without the discomfort of other things (or people) getting in the way. The goal, then, is to seek balanced cognition: to recognize when we’re being impacted by our emotions, and if necessary, sitting with the discomfort that accompanies our decisions. As Blakeley says, “You don’t have to believe what you feel.”

- Be on guard for defensiveness. When we come up against opinions that contradict our own, or when we receive feedback about our approach, it’s all too common to feel personally attacked and get defensive. The same is true when we’re confronted with an uncomfortable situation like declining sales–it can provoke anxiety that trickles down to the rest of the organization, creating a culture of fear and self-preservation. To avoid this, depersonalize the feedback, and remember that setbacks and failures are just another part of learning. You must also look out for defensiveness in managers throughout the organization. Performance management can be uncomfortable, and as a result, leaders are sometimes unwilling to defend the values (e.g., openness) of their organization when they’re endangered.

- Integrate information, then act. Reality, of course, is much more complex and nuanced than any one person can possibly comprehend—which is itself an uncomfortable feeling. If we don’t have a firm grasp on what’s going on, we feel out of control, and reach for simplistic answers. That’s why your goal as a leader is to remain humble and constantly expose yourself to other peoples’ realities, attempting to create a richer and more accurate representation of reality. This requires not just listening to others, but also taking the time and space to assess what you’ve learned, such as going on a retreat or meeting with a coach. At the same time, your mental model will never be complete: you’ll rarely be able to make a decision knowing every possible factor, so don’t let information gathering turn into procrastination. In a complex or chaotic environment, sometimes the best decision is to act, and use feedback to iterate.

- Embrace tension. When conflict or discomfort comes up at work, we tend to want to resolve it as quickly as possible. And in fact, as leaders move up the hierarchy, it becomes easier and easier to avoid these feelings, as we can delegate these unpleasant tasks to others, or surround ourselves with people who agree with us. But we often need some extra push to overcome inertia—to be willing to change—and it very often comes in the form of pain, anger, or frustration. So the next time you sense tension, explore it. What’s causing the conflict? How can individuals involved get a deeper understanding of what the other is experiencing? Have you considered all potential solutions, or are you falling back on what’s worked before?

- Recognize conflicting motivations. Individuals are bundles of competing motivations, values, desires, and emotions. A proposed change might get us closer to one goal (such as a promotion) while causing distress in another area (having to learn new skills), or even conflict with our values (skepticism about “office politics”). As you evaluate your choices, be honest with yourself: are you making a decision because it’s what you personally prefer, or because it’s the right thing to do? Living up to your ideals is hard, but instead of thinking of this task as wishful thinking or “not the real world,” think of it as a skill that can be learned, practiced, and improved on.