At NOBL, we help two kinds of clients: Goliaths and Rocketships. Goliaths are companies in which scale has ceased to be a competitive advantage and their increasing complexity actively works against them. Rocketships are companies in which explosive exponential growth (fueled by product market fit) threatens to shake the company apart and potentially devastate the promise of a new market paradigm.

The last month has been excruciating for Rocketships.

In 2013, Inc asked if Quirky was the world’s most creative manufacturer for making invention accessible to its 500,000 inventor network. This month, Quirky began bankruptcy proceedings.

Earlier this year, Leigh Gallagher of Fortune Magazine declared that the virtual assistant provider, Zirtual, had changed her life. This week, Zirtual abruptly (and without notice) laid off its entire staff before being hurriedly acquired by Startups.co.

“The numbers were just completely fucked.”

– Zirtual CEO, Maren Kate Donovan

In 2012, Taskrabbit declared that the grocery delivery service Good Eggs would be the future of the local food movement. Just last week, Good Eggs announced it would lay off all staff outside of San Francisco and discontinue service to all other major cities.

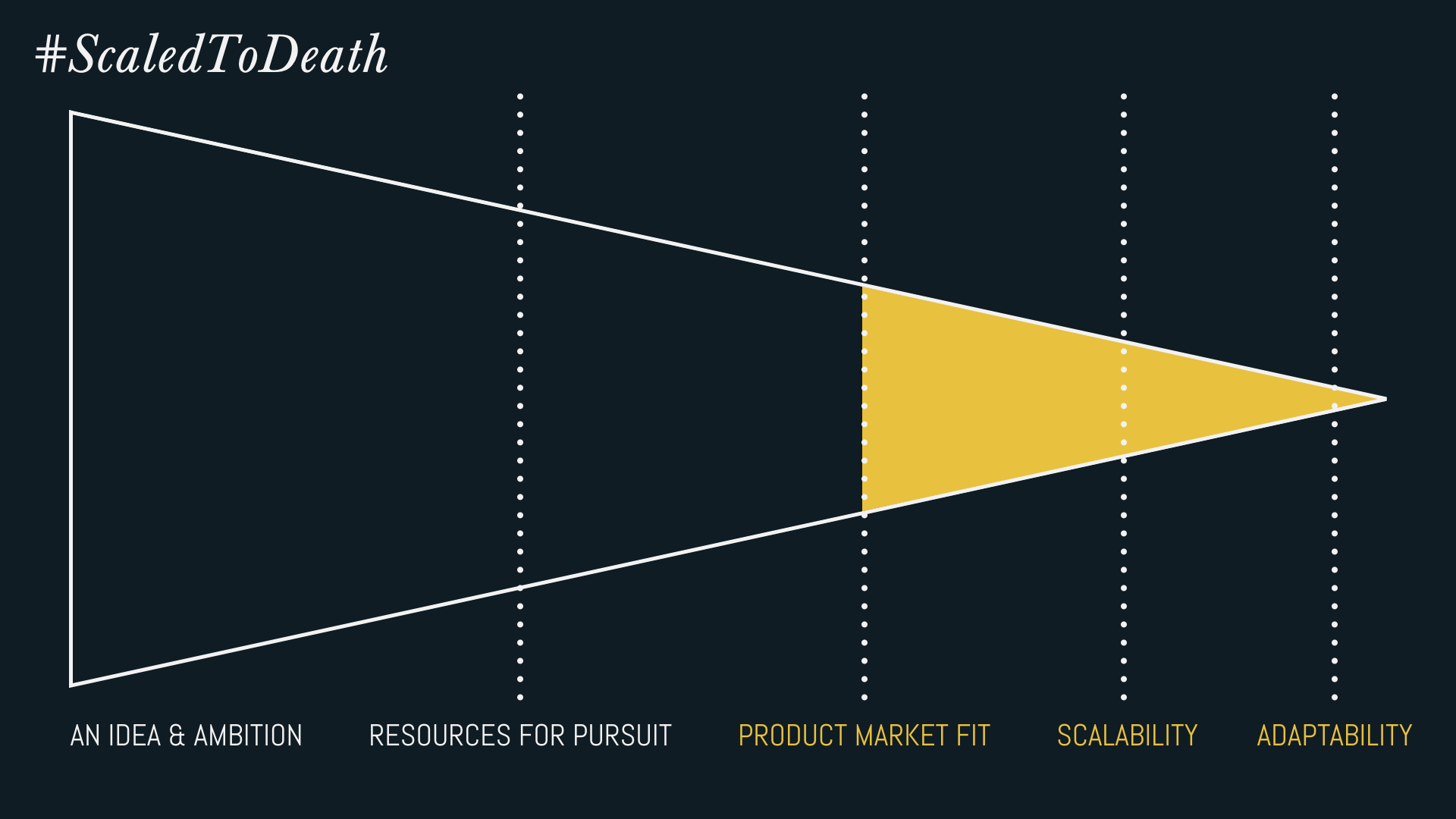

The majority of startups fail because they never find product market fit. They search and search for a viable product to successfully bring to market and simply run out of resources before they uncover it. But Quirky, Zirtual, and Good Eggs had found product market fit. In all cases, they had healthy customer bases and had produced successful products. The error, for each, resided in the choices they made in how they scaled the business.

For this year’s SXSW V2V conference in Las Vegas, we wanted to share why startups fail even after they’ve found product market fit. Drawing from our own clients and researching more than 40 firms that had either scaled woefully or gracefully, we’ve distilled the most frequent pitfalls into 6 categories:

- Business Meh-dol: lacking a shared understanding (or interest) in building a sustainable business model

- Disjointed Escalation: seeking growth that the firm is unprepared for

- Customer Amnesia: forgetting that the customer experience is paramount to a successful business

- Cultural Procrastination: delaying or ignoring practices critical to cultural health

- Founder Fatigue: a falling out or falling apart at the top level of the firm

- Premature Celebration: buying one’s own hype or celebrating the wrong end-goals

The goal of creating the list is to help startups scale consciously; to keep these conditions in mind as decisions are made (or left unmade). Rather than dictate how your startup should act, we’ve offered parables and questions for your team to unpack and discuss together.

While Quirky’s overall revenue was growing, its losses were mounting as well. And that’s because the business model at Quirky was, for many of its more ambitious products, fundamentally broken. Kaufman highlighted a number of stranger inventions that the company had created: a set of wheels to turn any object into a remote control car and a bathroom mirror that eliminates the fog from shower steam. The company had spent over $800,000 developing the products, but neither one ever made it to store shelves. These were not anomalies. Kaufman pointed to the Beat Booster, a wireless speaker and universal charging station that Quirky spent $388,000 to develop. At the time it had sold fewer than 30 units. And even when products did sell well, the margins were so bad the company often lost money. Quirky had paid out more than $9 million to the inventors who submitted ideas for new products, but it had lost more than $150 million in the process.

Source.

In 2000, I was the lead engineer for a venture-backed online startup. I was also 17 years old. I remember wondering how we planned to make money, but I remember those concerns being drowned out by us lauding our financing and celebrating our growing site traffic. Of course, we eventually went bankrupt (like so many others) due to our downright lack of a business model. Personally, I learned a valuable lesson and I thought that lesson was universally shared as well — yet we still see so many examples of startups (and their VCs) that confuse revenue with profit and readily sweep losses under the rug of self-assured scale. Startups by no means have to turn a profit on day one of the business, but the losses it will accrue should be strategic.

For your team to discuss:

- Do we know and can we recite our basic financials? Start with the cost to acquire customers, the estimated lifetime value of those customers, the time it takes to realize that value, cash on hand, and the current burn rate. If we don’t know the answers to these questions, why and what will it take to make our first assessment?

- How often should we review our finances, for what reason, and who on the team should participate? Are we using our finances to forecast the health of the business and have we instituted financial triggers (e.g. hiring and firing) based on the financials? How open versus closed are we with the books and why?

Fab sources estimate that moving into Europe prematurely cost the company $60-$100 million. There were too many employees and not enough sales generated. Streamlining the businesses was difficult; there was no US playbook to hand over to Europe. Additionally, Fab spent $12 million signing a 10-year leaseon a warehouse there that eventually closed.

Source.

For startups that have found product market fit, indicators of scale become themselves, markers of success. Founders are eager to tout how many countries they’ve entered, how many customers they’ve acquired, how many employees they’ve retained, and how many products they’ve sold. Yet, each of these decisions has a dramatic impact on how the business operates, many of them unintended and unforeseen. Most of the failed startups we studied found product market fit through trial and error, making small bets and doubling down when they had success — yet when it came to scaling the business, they made big, unsafe bets without understanding their consequences.

“The single biggest mistake we made was growing too quickly, to multiple cities, before fully figuring out the challenges of building an entirely new food supply chain”

– Good Eggs CEO, Rob Spiro

For your team to discuss:

- How can we test and learn our way into scaling the business? How can we assess the costs and impacts of that growth on all areas of the business? How can we take measured steps forward without risking what we’ve already built?

- How do we ensure that our support systems can grow inline with the business? Can our current HR, customer service, financial, legal, and decision making systems support exponential growth (hopefully without having to add exponentially larger resources)? Can we find outside partners or redesign our internal systems for rapid change?

The short answer to why Friendster failed is the news feed — or rather, Friendster’s lack of one. I remember first logging on to the site, and seeing a big empty profile to fill in with photos, personal details, interests, and the like. But once I had a meaty profile (right down to my timely lamenting of the end of Buffy the Vampire Slayer), the next thing to do was… what, exactly? Sure, there were testimonials for friends, but after writing the half-dozen or so I actually wanted to write, it seemed that the only thing to do on Friendster was polish my profile. […] Then Mark Zuckerberg and his team stopped playing around. Zuckerberg rightly recognized that Facebook’s news feed was the key to its long-term success. While the site was still attracting new people, he revamped it to elevate the news feed’s importance, pushing apps and boxes to the rear and putting friends’ updates, shares, and discussions front and center.

Source.

Product market fit is neither absolute nor eternal. The lower the cost to entry in your market, the more customer obsessed you must be. Moreover, customer obsession must come before competitor obsession or you risk missing a completely new (and significantly) more valuable opportunity.

It turns out there was another app that shared a similar vision (to Gowalla) called Burbn. They were building yet another check-in type service loaded with every feature but the kitchen sink. But early user feedback, coupled with a desire to avoid the check-in battle shitshow already in progress, led them to drop everything to focus on one simple feature: photos. They made the act of taking and sharing photos (many of which just happened to be location-tagged) fast, simple, and fun. They made their own rules. They called it Instagram.

Source.

Gowalla lost the check-in war and sold to Facebook for roughly $3 million. Instagram, by listening to their users, bypassed the check-in war and sold to Facebook for $1 billion.

For your team to discuss:

- How can we ensure continued customer obsession as we scale? How do we define an explicit rhythm and expectation for testing and learning with users? Are we able to see into how our current customers are adopting and adapting our products/services? How do we know when to scrap the current product and start over based on user feedback and will we have the courage to do so?

- Are we too obsessed with our competitors? Have we taken too much from existing players? Are we playing the wrong game or by someone else’s rules? If so, how can we refocus teams and products?

I watched alcoholism and substance abuse skyrocket, relationships crumble (including my own), people slept on office couches, two developers got divorced, one nervous breakdown. They attempted to smooth this over with more stock, free food and t-shirts. Free food doesn’t do you much good when you’ve lost fifteen pounds from not eating. Our game shipped and performed rather dismally, so the bonuses, raises, promotions and rest we were promised didn’t materialize. With a now completely exhausted team, we were expected to work even harder to improve key metrics.

Source.

Culture is far more than fringe benefits, company outings, or recreational spaces. An organization’s culture is the sum of its shared behaviors, values, attitudes, beliefs, and assumptions. Culture is the shared reality in which work gets done. A reality that should bring stability to teams, projects, and the business overall.

There is nothing that is more important than team, culture, and values. It is the glue that holds the whole thing together for the long haul.

– Fred Wilson, venture capitalist

Cultures are organic. Cultures emerge. But they can also be intentional. People can be thoughtful, purposeful, and responsible around the behaviors, values, attitudes, beliefs, and assumptions they share. Organizations can be empowered to design the culture they want. Instead, the failed startups we studied too often ignored their culture and signals of its declining health. Like Zynga, they put growth ahead of everything and everyone else — and the costs to their people and to their culture doomed the business.

Plan your culture early. Think about (and document) the things you care about as a group, the way you work and make decisions.

– Eric Schmidt, Executive Chairman of Alphabet

For your team to discuss:

- Does culture have a seat at our leadership table? Is culture a topic of discussion at our leadership meetings and/or is someone on the leadership spearheading its health?

- Are we building an intentional culture, and if so, how are we measuring it? What kind of culture are we dedicated to creating? What should it look and feel like to work here? Are we living up to those ideals and what value are they generating for the business?

We’re not sure how to adequately express our shock and disbelief at the news that Jason Russell, one of Invisible Children’s co-founders and the star of the Kony 2012 campaign, was taken into custody last night for drunkenly masturbating in public. […] Jason Russell was unfortunately hospitalized yesterday suffering from exhaustion, dehydration, and malnutrition. He is now receiving medical care and is focused on getting better. The past two weeks have taken a severe emotional toll on all of us, Jason especially, and that toll manifested itself in an unfortunate incident yesterday.

Source.

As a culture, we revere startups and idolize their founders. But, like the rest of us, founders are fallible and exhaustible creatures. Moreover, many founders confuse productivity as their measure of success rather than the leadership and support of those around them. Compounding this, we also tend to conflate the accomplishments of the many with lone individuals — the iPhone was less Apple’s accomplishment than it was Steve’s, for example. Altogether, founders are expected to be sleep deprived, obsessive, isolated geniuses with god-like output.

Unfortunately, far too many founders try to live up to this cultural fiction and tank their companies because of it. Who you surround yourself with and how well you monitor and care for your well being dictate your ability to lead a growing company, not how few hours of sleep you need or how many meals you can skip before you can’t function.

For your team to discuss:

- Is our founder committed to self-care? Are they sleeping enough, eating well, and are they conscious to their behavioral patterns in the office? Or do they use maladaptive behaviors as coping mechanisms (if not badges of honor)? Who on the team can help monitor and advise them if they’re falling short?

- Have we hired to mitigate our founder’s short comings? Who is the Sheryl Sandberg to your Mark Zuckerberg — someone whom balances the founder and can still retain a transparent and productive interpersonal relationship? If someone like this doesn’t exist inside the company, can it be addressed by the board or an advisor?

Looking back, Donovan says her two big mistakes were not having a full time CFO and not having a proper board.

Source.

How did a company with so much going for it stumble so badly? Agassi’s grand vision gave Better Place life, but according to former employees, investors, and board members, that same grand vision also ultimately destroyed it. Entrepreneurs are frequently told not to drink their own Kool-Aid — which is to say, to remember that the stories they tell about how their products will save humanity are just that. Privately, they are cautioned to focus on the small things; to make more money than they lose; to cut costs when needed; and, when necessary, to pivot to a more promising business. The caution seems especially important in a culture that increasingly celebrates startups, threatening to confuse their mythmaking with reality. Agassi made great Kool-Aid and then drank it all himself.

Source.

Premature Celebration is when the startups confuses a short-term win (like press or funding) for long-term viability of the business and/or when a founder or team buy their own hype and become deaf to challenges in the business. When we examined startups that had failed to scale, this mistake seemed to be the most personally painful for founders and their teams because they couldn’t shift the blame to a competitor or cultural force. This mistake is also at least as old as the myth of Icarus and like Icarus, begins with complacency and ends tragically because of hubris.

For your team to discuss:

- What’s our mission in the world and is it measurable? Do we know what we’re trying to accomplish together long-term and is it more than marketing copy; meaning, can we measure it? Are short-term wins (e.g. funding, press) giving us the false sense that we’ve accomplished that mission?

- Do we have and listen to objective outside counsel? Who will tell us when we’ve drank our own Kool-Aid and will we listen to them if they said so? How often do we engage with those voices and how can we make it a consistent conversation?

Learning From These Lessons

If you’re part of a business that is beginning to scale, we think these 6 mistakes and their discussion topics could be invaluable for your leadership team. We suggest breaking down each common mistake into a 60-minute discussion session and spreading these sessions out week-by-week (thus taking 6 weeks to cover all 6). Each discussion session should end with clear actions and owners for those actions. If you find the discussion valuable, we highly suggest repeating the cycle as the business continues to scale and encouraging leaders to conduct these sessions with their own teams, reporting back on their discussions.