Table of contents

Every large-scale transformation is born from a leader and a hunch: that things can be better, and that better is possible. Conversations ensue with other leaders, and a wave of ambition begins to crest internally. The question then becomes: where to start?

Common Approaches to Beginning Transformation

Pain can be a compass. Leaders often rush to where the dysfunction or dissatisfaction is most acute: a failed launch, a downtrodden team. Honing in on an issue can bring immediate relief and prove change is possible, but it also runs the risk of fixing merely a symptom. Worse, overly focusing on pain can distract you from tackling the harder, more systemic issues and responding to emerging threats.

Structure is (usually) a bad place to start. Years of research show that reorgs produce little of the desired effect, are often damaging to productivity, and create change resistance that will hinder other interventions.

You could also try a broader approach, adopting a comprehensive solution like a new methodology (e.g. SAFe) or platform (e.g. an ERP). This might be necessary, but can result in an awkward fit. Leaders then get waylaid by experts and dogma insisting they’re “not doing it right,” when really, they just have differing needs. In fact, the time and effort expended in forcing the organization to fit the ideal are wasted, as it’s irrelevant to the organization’s goals.

And that brings us to the final approach: deciding where to start based on the organization’s desired outcomes. Ideally, leaders would first define clear outcomes and build a set of hypotheses about which interventions are the “best bets” to influence those outcomes. Of course, this has its own risks: leaders can swirl for months trying to perfectly describe the organization’s goals, devolving into a series of meetings where colleagues copy edit one another and muse over synonyms. Or leaders might attempt to comprehensively “map” the organizational system or assess their readiness—which in complex systems like organizations, mostly produce a false sense of confidence. And as time ticks by with no real tangible change, the collective ambition for change and executive alignment recede.

A Better Way to Begin Transformation

So, again, where to start? We’ve found the answer is “all of the above,” but in moderation:

- Acknowledge pain points and remedy one or two pressing issues to demonstrate a commitment to making change. At the same time, leaders must remember these are just band-aids. In fact, they should be careful to pick interventions with discrete solutions because even a “simple” pain point can often be a systemic issue that requires a much bigger effort to resolve.

- Steal from systems. Don’t start with a massive investment in a big system or encompassing framework, but feel free to implement portions of it. You’ll often find ideas or components to experiment with that have already been through rigorous testing in other environments.

- Simplify how you define your outcomes. If you can convince others that an exhaustive process is unnecessary, you can define outcomes much faster and far simpler than the standard practice. Describe your goals just enough to align others into taking action.

When we’re kicking off the Change Making process, we use our Change Charter, and Organizational Domains and Levers for Change, below, to help leaders prioritize desired outcomes and balance demands.

The Change Charter

The Change Charter is a narrative-making and orientation tool we use to help organizations define outcomes and align teams toward the work ahead. We use it in the early stages of a change, but never aim to make it “perfect” or even “complete.” Instead, we strive for a working draft with plain language and just enough information to align folks to get started. We refine the Charter as we experiment with pain points and “best bets,” making it a living document that helps onboard new change participants and re-align teams when they get stuck.

The Change Charter typically includes:

- The reason why change is necessary, now

- A picture of what the ideal future looks like

- The benefit and costs of making the change

- Some semblance of a plan, including bets and probable roadblocks

- The players and types of people you can expect to encounter during the change

Organizational Domains and Levers of Change

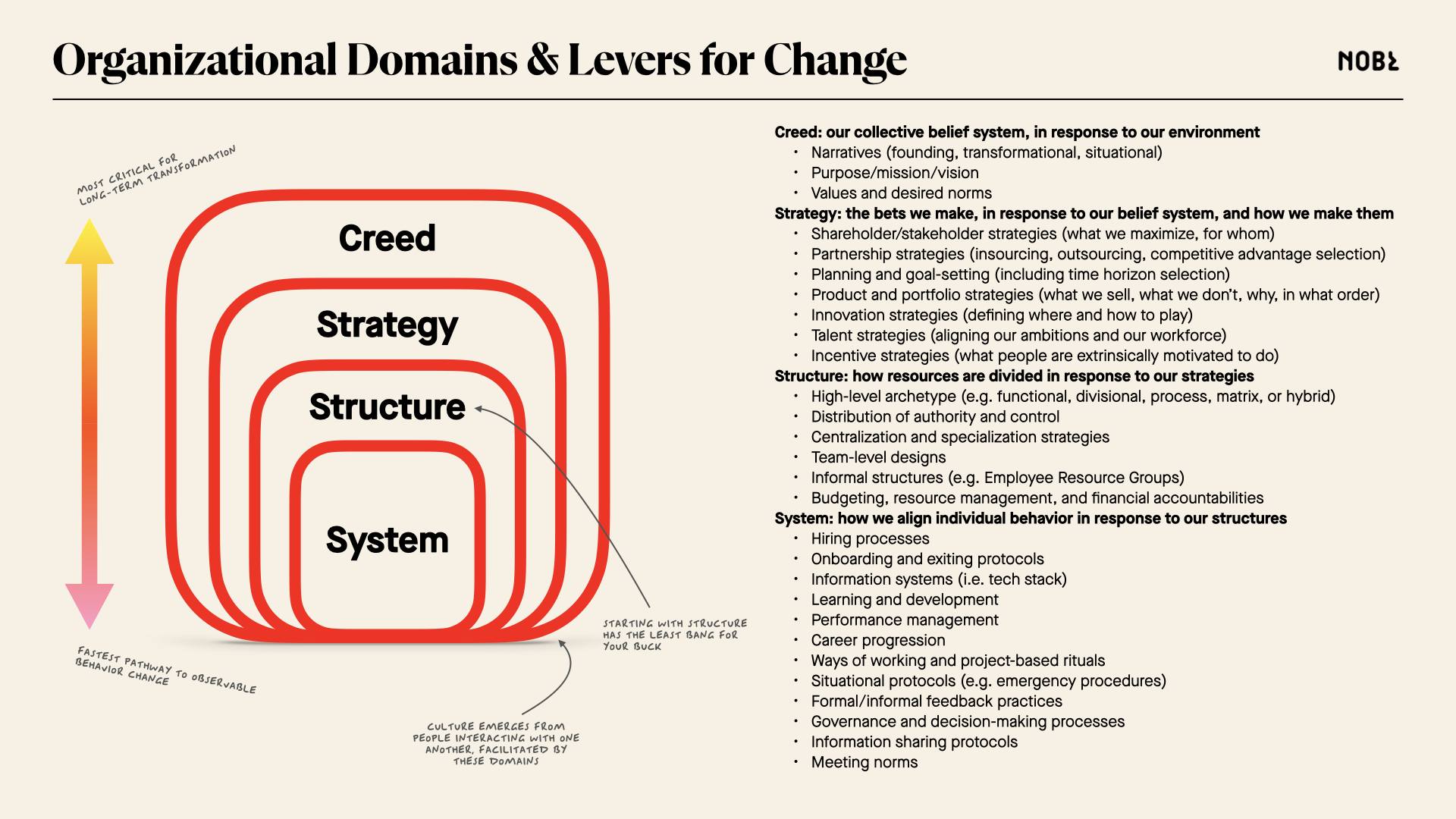

There are many ways to characterize an organization, but we’re partial to organizational domains, adapted from a Pulitzer Prize winning book by the business historian Alfred Chandler. It envisions organizations as a nesting doll, with each domain influenced by the one above it:

- Creed is the shared belief system that guides the organization through its environment. Belief systems can be cultural, inherited, even unconscious, but they can also be intentionally shaped in order to help guide collective decision-making and even quality control.

- Strategy consists of the bets we make along with how and why we select those tradeoffs and sacrifices, aligned with our Creed.

- Structure is how we divide resources in response to our Strategy.

- Systems consist of anything that works to align behaviors across structures.

Each domain can be influenced by different levers for change (what’s pictured here is hardly comprehensive). And based on the work of the Change Charter, we partner with our clients to select levers to experiment with in order to produce their desired Picture.

Selecting these levers, especially the very first levers to experiment with, is an educated guess at best—hence, the need for experimentation and learning. That said, our experience has taught us:

- The system bucket is often overlooked or deprioritized (e.g. “Really, we’re going to start by experimenting with processes?”), but the levers here can produce observable behavioral change quickly. Again, early traction is a powerful signal that leaders are listening and that change is possible.

- Structure is (usually) a bad place to start. Years of research show that reorgs produce little of the desired effect, are often damaging to productivity, and create change resistance that will hinder other interventions.

- True transformation—that is, changes that possibly upend the organization’s operations and even its core identity—cannot occur without interventions in the Creed and Strategy domains. This means that executive buy-in has to be considered from the start, including preparing those leaders to lose aspects of the firm they are comfortable with.

Ultimately, though, the “right” place to start is less important than getting started and staying committed to learning from the effort. Learn more in Starting Change: An Executive Guide.