Table of contents

Even in an era of constant change, planning has timeless benefits: it creates a venue for us to discuss the future, it helps us align goals across our teams and divisions, and it rallies us together behind a set of competitive ambitions. Planning isn’t dead, but it must evolve as reality continues to evade our best efforts to plan, react, or even comprehend it. And many companies (including our clients) are turning to scenario planning for that evolution. But what’s the difference, and when should it be applied?

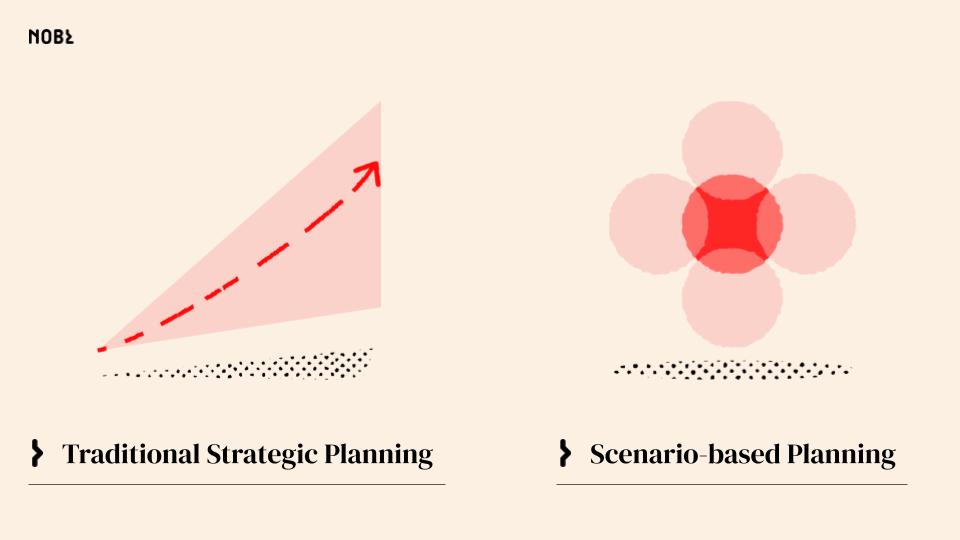

Traditional Strategic Planning vs. Scenario Planning

Strategic planning is the process of turning near-term ambitions into a set of tradeoffs and tactics. It answers the question, “How will we get from Point A to B?” This process assumes (sometimes too frequently) that tomorrow will be very much like today, though companies can tack on contingency plans or variances in their forecasts to account for uncertainties and unknowns–often as a final step.

In contrast, scenario planning begins with the unknown and the uncertain. And unlike strategic planning, scenario planning imagines multiple possible futures and then forces us to enter a discussion about what role to play in those futures. What can we do to shape more beneficial futures? What are the adaptations or minimum bets we need to make now to be prepared for the worst-case scenarios?

The Traditional Strategic Planning Process

A more traditional method of strategic planning might look like:

- We gather data about our firm and our environment, including financials, competitors, customers, technology, culture and more

- We synthesize that data into strengths, weaknesses, opportunities, and threats (looking both internally and externally)

- We define a set of realistic ambitions based on that synthesis

- We choose a set of strategies (aka tradeoffs) to achieve those ambitions

- We generate a list of tactics under each strategy

- We plan and resource those tactics along a timeline that includes measurable goals and milestones

- If a risk is foreseeable, we may develop a contingency plan to help us adapt to change

- We communicate these ambitions, strategies, and plans repeatedly

The Scenario Planning Process

Similarly, there many approaches to the scenario planning process, but it generally looks like:

- We begin by deciding the scope of the future to imagine: the time frame (e.g. five years from now) and focal issues (e.g. public health and public events)

- We identify the stakeholders and stake-seekers who will either affect or be affected in our scoped future and whose voices and perspectives should be incorporated into our process

- We compile a list of trends related to our scope by interviewing or otherwise involving our stakeholders

- PESTLE is a useful acronym here, representing the different drivers of trends and change: Political, Economic, Social, Technological, Legal, and Environmental

- Reflecting on our trends, we identify critical uncertainties (e.g. when will a vaccine be readily accessible? When will people feel safe attending large gatherings?) that will come to define, in one way or another, the future we are imagining

- Based on those uncertainties, we develop an initial set of possible future themes by starting with the very worst possible future, the very best, and a handful of surprising alternatives

- We gut-check these themes with our stakeholders and stake-seekers, not to determine which future is more likely, but to validate the logic behind these futures and to layer in nuance and context (thereby removing the truly impossible or irrelevant themes)

- Only then do we write our 3-5 final scenarios–each with a headline (e.g. The Virus Wins) and short story to illuminate the final conditions of our future and the events that got us there

- We may, at this step, elect to do further research and apply quantitative figures or models to our futures

- Then, reflecting on the scenarios we have developed, we determine our postures and plays:

- Posture is our strategic approach to a future: we can work to shape beneficial futures OR plan to adapt to potentially harmful futures

- Plays are the tactics we can take given our posture: big-bets for the futures we hope to shape, options which are minimal investments that will position us to more easily adapt to less-beneficial futures, and no-regret moves which will pay off no matter what happens (e.g. removing unnecessary waste from our processes)

- Lastly, we need to define a plan and process to routinely revisit and revise our predictions, our postures, and plays based on how reality actually unfolds

The Benefits and Risks of Planning

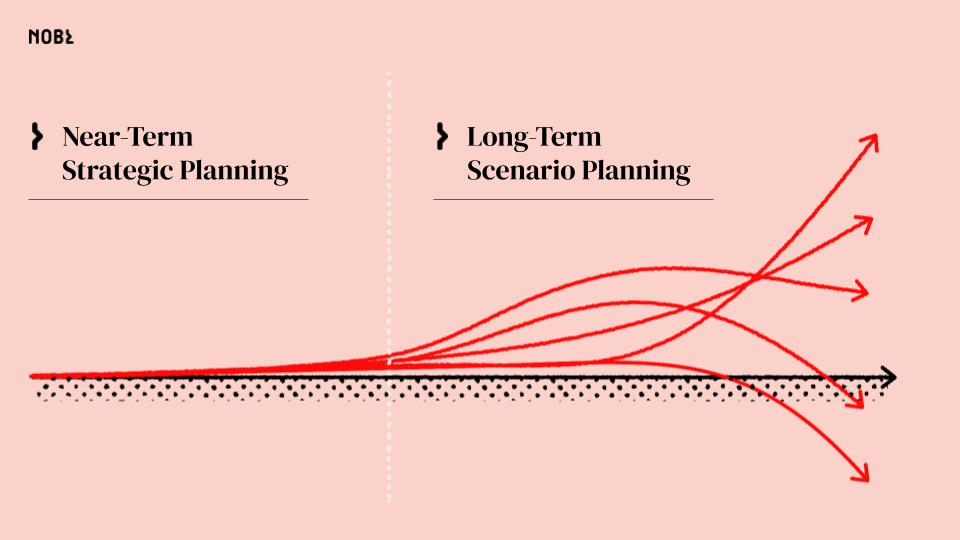

As is likely evident, traditional strategic planning is a great tool for near-term periods of relative stability. Scenario planning is better at helping unlock creativity by reflection on long-term, external uncertainties. It’s too simplistic (and plain wrong) to prefer one tool over the other, both are indispensable tools in our strategic toolboxes that are equally helpful at different times. Both, too, have their limitations. Regardless of which tool you’re using at any moment, remember these tips when formulating any plan:

- Our own biases are hard to see and harder yet to overcome. Therefore, we need to invite and include a diversity of perspectives in our process (both stakeholders and stake-seekers). Moreover, as companies mature they often form Strategy units who are frequently isolated from the realities of the business and/or suffer from the same group think as everyone else in the company’s culture. External strategic facilitators (yes, like NOBL) can help you overcome your biases and even help you permanently rectify your blindspots.

- A strategic planning process is less about the process itself and more about the conversations and decisions it forces. We routinely see teams wrongly focus their attention on ticking the boxes of a strategic process rather than spending the necessary time to arrive at a forum where the truly consequential, the inherently messy, and the long-avoided topics are discussed and finally processed as a team.

- A strategy is more than a plan, it’s a set of choices and tradeoffs designed to produce a desired outcome. Far too often, executives churn out Powerpoints and product roadmaps which only masquerade as strategy because they include no hard choices or sacrifices. We recommend obsessing over your strategic tradeoffs and formalizing them as “even over” statements. A good strategy is the result of a painful process of saying “no” more than saying “yes.” Moreover, a clear set of tradeoffs will be of excellent service when you need to prioritize and re-prioritize your team’s time and efforts.

- The final step in any strategic process should be to address possible change resistance. A new strategy will come with consequences for teams on the ground and it’s best to plan for how they will receive and accept those changes. Remember that a feeling of loss almost always accompanies a change.

These issues are exactly why we’ve developed an approach that incorporates elements of both Strategic and Scenario Planning. We call it Adaptive Planning, and it equips organizations to respond more nimbly in a changing environment: learn more.