As we discussed in our piece on how to build trust at work, trust is a choice to make yourself vulnerable, to give someone—a boss, a colleague, a direct report—some power over you. And unfortunately, that power can be misused or even abused.

We know that teams with high levels of trust experience a range of benefits, including 74% less stress, 50% higher productivity, 76% more engagement, 29% more satisfaction with their lives, and 40% less burnout. When trust is absent, therefore, the team suffers. Employees become unwilling to take interpersonal risks, and the functional behaviors that define teamwork (like collaboration, knowledge sharing, and cooperation) fail to materialize. Trust violations can even open the door to retaliatory actions from employees such as active disengagement, sabotage, or even theft.

Not only that, when trust is violated, people begin to question the organization’s values, their leadership’s integrity, and their own commitment to the institution. And in a time with elevated levels of uncertainty due to the pandemic, social unrest, and the changing nature of work, trust violations (if left unaddressed) threaten to fully unravel organizational performance.

The bad news is that even with the best of intentions, most teams will experience or be exposed to some form of a breach of trust. Even simple disagreements, when fueled by misunderstanding, can devastate trust. Leaders therefore need tools and strategies to address, repair, and monitor the levels of trust on their teams.

The Basics of How to Rebuild Trust

The good news is that trust can be repaired. People can commit to becoming more trustworthy and, given enough proof, others may allow themselves to be vulnerable yet again.

That said, there’s no universal process for repairing trust, nor is it easy. There may be common steps, including acknowledgment and action, but understanding nuance and being responsive to others’ needs are just as essential. Congruence and consistency also matter —a second breach, even if it’s just a fraction of the original violation, can reaffirm others’ suspicions of a pattern of malicious intent. In fact, confirmation bias might make it seem even worse, overshadowing any positive attempts to regain trust.

The context of the violation is also important. Trust lost early in a team’s formation is particularly difficult to repair, as there’s little else but the violation to go on. This is especially true in hybrid or fully virtual teams, where building trust may take longer or rely more on a transactional form of trust. And losing trust with your team (as opposed to with just one individual) is hard to recover from because it can position you as a common antagonist that the team can rally against. Therefore, special care should be taken when forming any new team to identify and respect boundaries and norms.

Finally, some researchers believe that instead of simply restoring the trust that had existed before a violation, the new trust that forms through a process of repair is of a different and less-pristine nature. It may be more akin to the transactional form of trust we discussed in our previous article. Nonetheless, that trust can still power a group of individuals to work together effectively toward a shared goal.

Scenarios and Suggestions for Repairing Trust

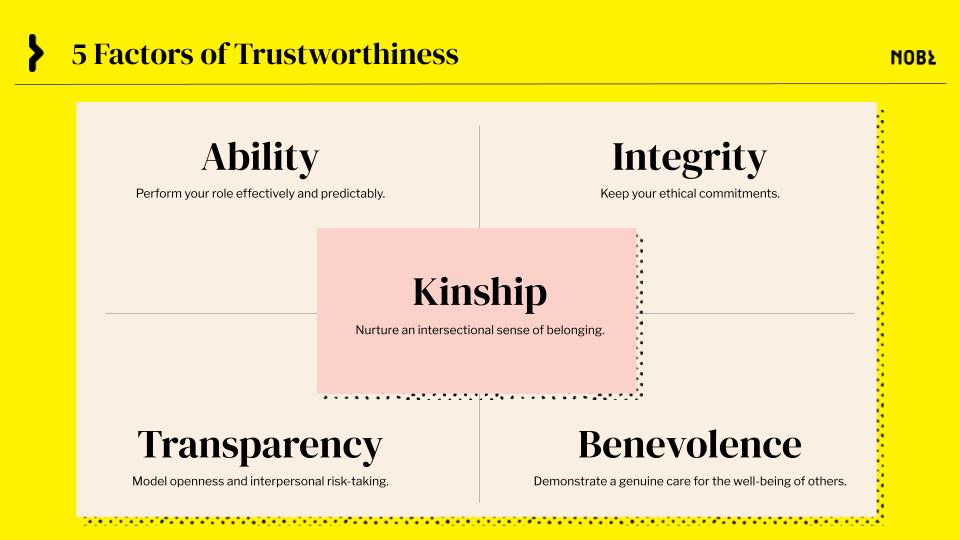

The work of trust repair is ultimately dependent on the kind and context of violation. The same categories that make someone trustworthy (ability, integrity, transparency, benevolence, and kinship) are also the categories that cause trust to be lost. If you find yourself trying to recover trust, first, reflect on what category’s been most affected. Then, take steps to acknowledge the harm caused, and invite others to respond.

We’ve identified some of the most common scenarios for broken trust below, as well as suggested approaches for repairing those relationships based on well-established practices like Nonviolent Communication and Restorative Justice. As you evaluate your situation, you may find it helpful to remember that although an apology isn’t always required to repair trust, it’s often instrumental in clearing the air and setting the stage for deeper understanding.

Of course, different cultures view apologies differently, both in terms of when they are owed and by whom (and these views are not always fair or equal among groups). The best rule of thumb is to apologize when you genuinely feel remorse for your actions, such as when you’ve clearly crossed a boundary, or failed to live up to a promise or clear expectation. After all, a half-hearted apology can actually reduce your trustworthiness in the eyes of others. If you choose not to apologize, however, do reinforce the value you see in the other person and your desire to restore the relationship.

When you’ve lost trust with a peer because you crossed a boundary or failed to deliver on a promise or expectation:

Adapted from Lewicki and Bunker

- First, acknowledge the violation. Don’t hope it goes unnoticed—it won’t—or expect to be forgiven without discussion. If possible, call yourself out before others have to. At the very least, don’t ignore the event or any hurt feelings. In many studies of teams, too few actually acknowledged trust violations, preventing recovery.

- Determine the cause. Understand why you breached someone’s trust to prevent repeating it. For example, you may have violated a peer’s trust by sharing something with your boss that they said in confidence to you. Maybe you did it because you thought they didn’t feel safe to share the feedback, or because you wanted to build rapport with your boss. Neither reason is an excuse, but they indicate different ways you must change to become a more trustworthy peer. You can share some of this context with your colleague, but don’t belabor the explanation or expect them to accept it. It may, however, help them understand your thought process, even if they disagree with its outcomes.

- Accept responsibility for the harm you caused. Ask your peer to describe how your actions made them feel, and admit that your actions did indeed cause that harm. Don’t lead them to believe that they manufactured their feelings out of nothingness, and avoid the political apology of “I’m sorry you felt bad,” as if to detach your cause and their effect.

- Commit to restorative actions and keep your promises. Detail the actions you’ll take in the future to restore their trust, and seek their ideas and input for any additional actions or remedies. Most importantly of all, stay true to these promises, and don’t expect any single act will restore your good name.

When you’ve lost trust with a peer, but the cause appears to have been a miscommunication of some form:

Adapted from Nonviolent Communication, which can also be used when two members of your team have lost trust, leading to dysfunction and distraction

- Start by seeking to repair. If you’ve been told, or can tell that you have eroded trust with a peer, acknowledge the event and express a desire to seek understanding and restoration in the relationship. Create an opening for the process, but don’t dictate time or terms: give them their own time to process and come to the table. It may also be beneficial to have an objective third-party facilitate the conversations.

- When your peer is ready, ask them to describe the facts of what occurred. Ask them to reserve their judgement and reasonings (for a brief moment only) to describe what they observed (e.g., “you didn’t respond to my email when I said it was urgent” vs. “you were ignoring me and belittling my issues”). In turn, do the same yourself. At this stage, you don’t need to agree on all the facts—the goal instead is to find some form of common ground to explore the conflict further.

- Then, allow your peer to share how those events made them feel (an emotion or sensation, rather than a thought), and in turn share your feelings. Own your own feelings instead of ascribing feelings to others (“I felt frustrated and isolated” versus “I was annoying you”). If you need to share how you think the other person may have felt, try using a phrase of Brené Brown: “The story my brain told me is …” such as “When you didn’t reply to my email, the story my brain told me is that I was annoying you.” Use that statement to test your hypothesis, and listen to what was actually happening for the other person.

- Next, focus on the needs each of you had in the situation that were unmet. A need could be “to be heard,” or “to have autonomy.” When discussing needs, try to stick to universal concepts rather than dictating preferences or specific forms of action: for example, “to be heard” is a universally recognizable need that you can connect with, versus demanding “a response to my email within 10 minutes.” The goal here is to recognize that most of us have similar needs, and would want others to respect those needs whenever possible.

- Lastly, discuss your requests for the future. Focus on concrete actions in the form of “would you be willing to …?” Remember, however, that a request is not a demand, and endeavor to be clear, actionable, and feasible. Discuss together and commit to reviewing whether these requests have been followed in the next 30 days.

When, as a leader, you’ve lost trust with multiple team members:

Adapted from Restorative Justice practices

- Assemble a group of those impacted, and acknowledge your violation and your commitment to repair. Again, don’t pretend to be sorry or offer excuses as you gather this group. It’s best to spend time before this session in self-reflection so that you can be present and less reactive to feedback.

- Start by asking members of the group to share more about the harm you caused, and promise no retaliation in response. Ask folks to share their observations and reactions. Let the group talk uninterrupted, without rebuttal. Clarifying questions should be asked only in good faith, and no reprisals should come after this discussion. You may explain, briefly, the intentions behind your actions, but again, don’t belabor an explanation or expect others to understand or value them more than the outcomes of your actions.

- Acknowledge the harm you caused. Take ownership of your actions and their consequences. Additionally, name the commitments you intend to take to restore your trustworthiness. These should include actions as well as explicit policies and measurable outcomes. Don’t ignore any necessary changes to the organization’s infrastructure.

- Invite members of the group to build on your commitments and develop their own requests for change. You don’t need to address each request in the moment, but you do owe the group a timely response of what you can and cannot commit to.

- Pick a date 60-90 days out to bring the group back together to reflect on your commitments (and put it on the calendar during the first meeting). Share any updates, but then invite discussion and listen again without reprisal or rebuke. Focus here on the effectiveness of any reforms made, and not just their intent.

As a leader, when an organizational change you’ve made has eroded trust in you and/or the organization:

Adapted from Rosabeth Moss Kanter

- Recognize that change is loss. Change, even when it’s for the best, triggers feelings of loss, including a loss of pride, narrative, control, familiarity, expertise, and even time. Moreover, an organizational change can feel like a violation of integrity or transparency, and can call the organization’s benevolence into question (i.e. Will this change lead to a layoff?). Be open to the fact that others will experience the change differently from you, especially if you’re in a position of power.

- Acknowledge any harm caused by the change. Walk through the checklist of losses with members of your organization and listen to their experiences. Admit to both the harms accepted as a necessary sacrifice, as well as the unintended harms caused by poor planning or communication.

- Allow for feelings in response to the change. An old change adage is that “you can feel any emotion during change, except for confusion—confusion means the change was poorly planned and executed.” If a true violation of trust has occurred, you likely need to spend time, including through listening circles, letting people share their feelings about the change with you.

- Demonstrate support in response to loss. Make a commitment to your teams to confront their feelings of loss. If they feel a loss of pride, recognize their contributions that got you where you are now. If they feel a loss of expertise, commit resources to their training and development, and so on. Additionally, commit to learning from the experience to improve the process of change in the future.

When, as a leader, two departments or teams below you have lost trust in one another :

Adapted from Amy C. Edmonson and Nonviolent Communication

- Begin with each team’s leaders. More often than not, teams are following their leader’s example in how they minimize, scapegoat, and even ostracize other teams. After all, trust is predominantly tribal, and under-performing managers often stereotype other teams in order to excuse their own failures. Leaders of such teams need to first enter a facilitated process akin to the nonviolent communication strategies listed above in order to gain a deeper understanding and establish new shared norms. As their leader, your role is to enforce these new norms and tamp down finger-pointing and dysfunction.

- Next, enlist their teams in exercises of understanding and empathy. We often lead teams first in a set of project retrospectives to establish their own facts and observations. We then share those observations with the teams they collaborate with most to encourage perspective seeking. We ask corresponding teams to review challenges and blockers in order to empathize with their partners and their needs.

- Then, look for an opportunity to work together in a new way. Identify an initiative—ideally one that has lower stakes or a flexible timeline—and hold a kickoff to establish new guidelines for how teams want to work together. Teams may find it helpful to develop user manuals that address topics like “how I disagree” or “how I’m often misunderstood” so that they reinforce both the habit of self-awareness and understanding others’ perspectives.

- Support cultural brokers. As the work progresses, some individuals may naturally start acting as “go-betweens” for the teams: either as “bridges,” who can translate team needs, or as “adhesives” who connect people and build relationships. Encourage this behavior and find more ways for individuals to get exposed to how the other team works.

- Check in on progress. Finally, hold regular check-ins with leaders and teams to see how work is progressing and address issues before they have time to fester.

When, as an executive, you’ve lost public trust in your organization:

- Acknowledge the numerous constituents affected by the violation. Not only may customers and members of the community lose trust in your organization, but employees will also see a public violation of trust (and the corresponding reputation hit) as a destabilizing event. Researchers have found that breaches of public trust can cause executives to detach themselves from the organization, both in terms of their identity and commitment. This detachment not only impacts factors like performance, but also causes leaders to double down on ethical violations, as they can more easily compartmentalize what the organization is doing versus their own personal culpability.

- Embrace real reform and accountability. In response to crises like the Enron scandal and BP gulf spill, researchers have outlined seven steps to repairing trust in institutions after a breach in trust (specifically in integrity). These steps are valuable to all constituencies:

- Establish an open investigation into what occurred. If possible, hire an external partner with credibility of their own to conduct the investigation. Allow them to share their findings with the public.

- Demand an accurate explanation. Publish the findings from the incident without adding political spin or legalese.

- Apologize and act. Admit fault and commit resources to those harmed.

- Replace senior leaders. Remove those responsible for the violation, swiftly and without contradictory messages like public praise or large compensation packages.

- Adopt both systemic and cultural reforms. This looks like rewriting incentives, creating new roles that monitor for future ethical breaches, and instituting new norms and policies across the organization.

Responding to a violation of trust

If you were the one harmed in a breach, you ultimately hold the power over whether trust can be repaired. The other party may go to great lengths to signal a commitment to restoration and trustworthiness, but the choice to make yourself vulnerable again is yours.

Withholding trust (and holding onto a grievance) may affect you negatively over time, though. Keeping yourself in a situation where you feel at risk can lead to stress, emotional harm, and social isolation. Exercise your own judgement, but note that sometimes the kindest thing you can do for yourself is to forgive. If forgiveness isn’t possible, and resignation isn’t either, focus on your needs instead of forgiveness (e.g. clear communication, fair compensation, etc.) and explore strategies to have these met.

Trust is an act of leadership

Acknowledging that you’ve broken someone’s trust is never a comfortable activity—which is why it’s actually a courageous act. Acting with humility, owning your actions, and moving quickly can all help minimize the damage to a relationship, or at the very least, begin the act of reconciliation sooner.